Women’s Suffrage Progress and Shortcomings

Celebrate, remember, and learn

Few Americans today would question that women have a right to vote in government elections, from local school boards to the president of the United States. It took nearly 70 years of activism before that right became law, with adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

But in truth, many women still did not gain the right to vote in 1920. August, National Women’s Suffrage Month, provides an opportunity to mark women’s suffrage progress and shortcomings.

The official fight for women’s right to vote is typically seen as stretching from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention until final adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed by Congress on June 4 1919; ratified on Aug. 18, 1920, when Tennessee became the 36th and final state to ratify the amendment; and signed into law on Aug. 26, 1920.

What has often been underreported in coverage of the movement is how people of color were left behind.

The Shortcomings

The women’s suffrage history that most of us learned looks at the brave white women who fought for voting equality … for other white women. Like much of the history we’ve learned, it’s told from the point of view of the winners, of those who call the shots in government and society.

The darker reality behind the women’s suffrage movement was that brave Black women fought for women’s right to vote, too. The movement started out with many whites and Blacks working side by side toward the same goal.

“The U.S. women’s rights movement was closely allied with the antislavery movement, and before the Civil War Black and white abolitionists and suffragists joined together in common cause,” says the National Park Service in “African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment.” Formerly enslaved and free Black women, including Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, and prominent Black men, including Frederick Douglass, worked in collaboration with white abolitionists and women’s rights activists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony.

“The U.S. women’s rights movement was closely allied with the antislavery movement, and before the Civil War Black and white abolitionists and suffragists joined together in common cause,” says the National Park Service in “African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment.” Formerly enslaved and free Black women, including Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, and prominent Black men, including Frederick Douglass, worked in collaboration with white abolitionists and women’s rights activists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony.

But then came the Civil War; the defeat of the Confederacy; and the passage of the 15th Amendment – which gave Black men the right to vote. (That right was effectively minimized through literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other methods for refusing Black men the vote). In this climate, the white voices wanting to mute the voices of newly freed Blacks drowned out the voices for racial equality. White suffragists saw a need to compromise. They would give up supporting Blacks in exchange for the support of racist whites.

A Racially Divided Agenda

In reality, well-known suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed voting rights for Blacks or people of color of either gender. Treva Lindsey, historian and professor at Ohio State University, explains,

After the Civil War, Stanton and Anthony used the National Women’s Suffrage Association’s publication, “The Revolution,” to propagate racist and xenophobic rhetoric, which in effect severed any semblance of solidarity with many African American, Chinese and recent immigrant suffragists … Stanton wrote, ‘American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters … demand that women too shall be represented in government.”

White women, that is.

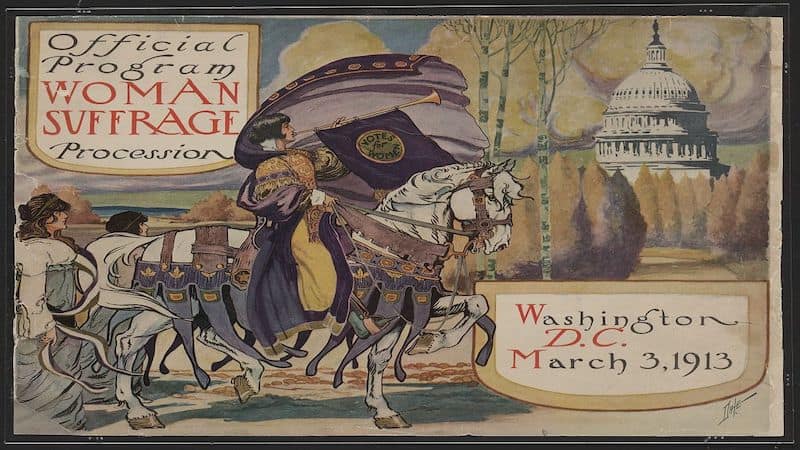

One of the women who traveled to march in the first suffrage parade in Washington D.C., in 1913, was Ida B. Wells, African American writer and activist. “On the day of the parade, she and 60 other Black women arrived to march with the Illinois delegation, but were immediately advised, as women of color, to march in the back, so as to not upset the Southern delegates,” notes Suffrage100MA, a nonprofit established to commemorate the anniversary of the 19th Amendment. “Wells-Barnett refused, arguing: ‘Either I go with you or not at all. I am not taking this stand because I personally wish for recognition. I am doing it for the future benefit of my whole race.’”

Slow Progress

After the adoption of the 19th Amendment, “White suffragists whom women of color worked alongside for decades largely abandoned the movement for voting rights,” says Lindsey, specifically of Blacks, Native Americans, and Chinese immigrants. African American women continued the fight.

Fortunately, many of the exhibits that celebrated the anniversary of the amendment take a wider view of the story.

The #BallotBattle exhibit at The Valentine museum in Richmond included the stories of Black leaders in the movement: John Mitchell Jr., editor of the African American newspaper, ‘Richmond Planet,’ and advocate for universal suffrage; and Maggie Walker, Black business leader and educator. The exhibit reveals the other side of the battle; this includes propaganda from the Virginia Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage, which stokes racial fear and appeals overtly to white supremacy.

In a flier entitled “Virginia Warns Her People Against Women’s Suffrage,” the VAOWS charged that if Black women were able to vote, “Twenty-Nine Counties Would Go Under Negro Rule.” The VAOWS argued in a separate piece, “More can be done for the advancement of the highest interests of the race by the influence of women free and unfettered by political ties and obligations.”

Unseen Views

A temporary exhibit at the Library of Virginia in 2020, We Demand: Women’s Suffrage in Virginia, included the experiences of Black women and the racial tensions that divided activists. The fear of allowing black women to vote highlighted the racism of many Virginians (including many suffragists). And these racist attitudes, as revealed in the exhibit, were more overt in the early 20th century than they are today.

So the centennial of the 19th Amendment was worth marking. It was worth commemorating. It was even worth celebrating – but we also need to recognize the weaknesses and flaws of the movement and the shortcomings of the amendment. Only if we recognize the progress that had yet to be realized can we best continue the march forward.

Opportunities to Commemorate Women’s Suffrage Progress and Shortcomings

Exhibits throughout the U.S. commemorated this major milestone. Boomer Magazine addressed the history and recognized sites in Virginia and in D.C. that marked the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Virginia Suffragists Battled for the Ballot Box, by Rene Sklarew

Suffrage: Virginia-Focused Milestones timeline, by Renee Sklarew

Lucy Burns Museum and the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial in Fairfax County, Virginia

Initially published August 2020; updated August 2022 to remove dated references to exhibits and add link to history of women’s suffrage in Wyoming in the 19th century (with thanks to a student, Grace, for sharing this link with us at Boomer).