The Magic Behind Stage Sets

Bringing a show to life at small venues, major productions and on the road

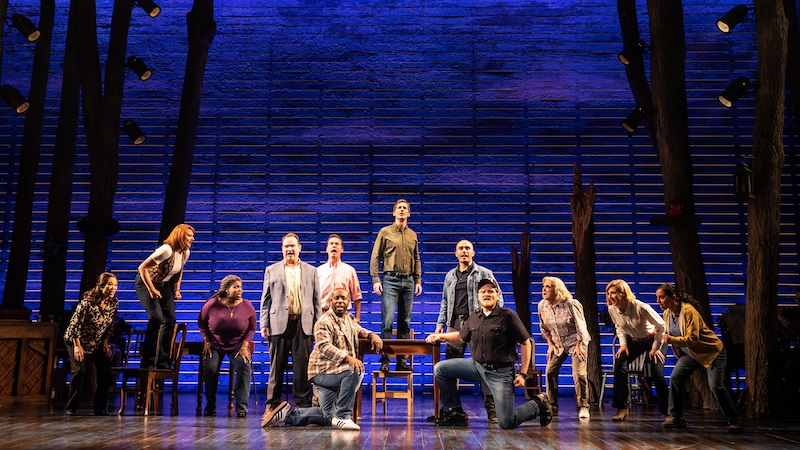

Creating an illusion that becomes reality for an audience isn’t an easy task, but it’s one that takes place behind the scenes of any artistic production. Different arts organizations tackle this backstage smoke-and-mirrors waltz of crafting stage sets in different ways.

Steve Sweet, operations and technical director for Altria Theater and Dominion Energy Center

“At Altria, we don’t build sets that we have to nail together and paint. Broadway shows come fully self-contained. Everything they need is inside their trucks,” says Sweet, noting that a lot of logistics go into putting on a show.

His team begins preparing for a traveling Broadway show at least a month out, especially with mega-productions like The Lion King, an 18-truck show. “We talk about how they fit into our place and the rigging that has to work with our grid and rigging system. That is a big component of the Broadway shows – how they attach and get their footprint in our space,” he says.

Some shows may need up to 80 local stagehands, which Sweet has to coordinate. “Some of the stagehands have to have skills in rigging or other skill sets,” he says.

Show load-in varies on the size of the production. A three-to-five-truck show can be loaded in within a single day while a 13-truck show like Wicked takes 2½ days to load in. “The Lion King is different. It takes five days to load in and three days to load out,” says Sweet.

Larger concerts operate the same as Broadway in that they are self-contained. Some of the smaller concerts at Dominion Energy Center and Altria can be different, he says. “The band may be flying in and we have to provide everything. They rely on us to make sure we have the equipment they need.”

Neil Mazzella, chairman of Hudson Scenic Studio and Hudson Theatrical in Yonkers, New York

Mazzella and his staff have built stage sets for over 400 Broadway and touring productions, including the tours of Hamilton and Fiddler on the Roof that come to Richmond this Broadway in Richmond season.

“We have shows all over the world,” says Mazzella.

Touring stage sets are a variation on the theme of the Broadway production, he says. “You have to work in the economic format of the road.”

His company looks at everything from the number of trucks to load-in time. “You also have to think about durability,” he says of the set. “When you build a Broadway show, it’s for a specific theater. A tour is in theaters around the country. It has to be cookie cutter when there are no cookies to cut.”

A set may have to be pushed up a hill or go down a ramp to get into a theater. Some are transported on elevators. “We have a good team of people that are always checking out the venues. Everything has to fit in the loading doors and the trucks,” Mazzella says.

When he’s working with a tour, he makes sure he knows the tour routing and the theaters it will play. Altria Theater has never come up as a concern, he says. “Load-in is average there, and their local crew is good.”

Nathaniel Shaw, artistic director, Virginia Rep

The design process at Virginia Rep begins about four to five months before a show opens. “It typically starts with a director expressing a vision for a show. It could be visual inspiration or important thematic ideas or context – the world in which they want to tell the story,” Shaw says.

Research material and imagery are pulled together in a collaborative process between the director and designers. “From that they can hone in on the visual representation of the themes and ideas the director hopes the production will communicate,” Shaw says. “The story drives a lot of the directorial decisions unless the director and designer have agreed on a highly conceptual production.”

The capabilities of the venue, budget limitations and the reality of the calendar “collide with the imagination of the creative team, and that is where the truth lies,” Shaw says.

The production team starts building stage sets eight weeks before opening night. While they may look as if they are constructed similar to home construction, sets are often propped up backstage by boards, planks and support systems, all of which have to meet safety standards. “Safety is first and foremost,” Shaw says.

Some shows require special attention, such as last season’s production of Once, which was co-produced with Fulton Theatre in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. “We knew that set would have to be struck and loaded into a truck, transferred and put back together by our team,” says Shaw. “It had to be designed and constructed so it could be taken apart in segments, labeled and put back together in another venue.”

The theater’s touring model, Virginia Rep on Tour, relies on the cast for setup and strike down. The set has to be “durable because it has to be done over and over again in schools and venues across the country,” Shaw says.

Phil Hayes, assistant technical director for the University of Richmond Department of Theater and Dance

Hayes, who received the 2019 Kennedy Center Medallion by the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, designs sets for UR and other theaters.

“The designer will come to me with drawings of what the set is supposed to look like. I put them in a working design,” he says. “Then we start building.”

Hayes often uses thinner boards unless the designer calls for sheet rock in the design. “Then we use two by four construction,” Hayes says. “Some sets will be covered with muslin and painted over so it’s really light. A lot of touring shows will use muslin. It’s lightweight, but it can rip if something catches it.”

Most sets are built the same way as a touring show. “You have to keep your restraints and your scale in mind,” he says.

Stage sets are normally built in four to five weeks and torn down after the show closes. “All that work for four days and then it’s gone. You can’t get attached,” he says.

Tom Width, artistic director at Swift Creek Mill Theatre

Sometimes the scenery “is described by the author of the play and sometimes it’s left to the producer to make those decisions,” Width says. “Our own set designer, in consultation with the director and producer, will determine how the scenery will serve the production in our space and with our resources.”

Once the scenic design is established, the theater “can usually build a set from start to finish in three to six weeks, depending on the complexity of the design,” Width says.

All of Swift Creek’s Youth Theatre productions take place simultaneously with its mainstage productions. “The designs for these two shows must be compatible, because we change back and forth between the two productions six times a week,” Width says, noting it doesn’t affect the selection of mainstage shows.

Tracie Morin, production manager for Richmond Ballet

The Ballet’s process begins with the “choreographer [creator of the new work] and the set designer meeting to discuss the vision of the piece,” says Morin. “This is probably the most time-consuming part as it could take months for them to settle on the design. Partway through the process, they will begin to include the artistic director.”

Once a concept is approved, it’s transferred to the production department, which executes the creation of the design. It’s up to the production department to create a budget “on the best way to bring the vision to life,” Morin says.

With ballet especially, quite a few things are “designed for drops [a hand-painted soft drop cloth],” Morin says. “If it is a drop that needs to come into existence, we reach out to receive bids on the construction and painting of the drop.”

It’s up to the technical director to keep “everything on target,” Morin says. “Every decision is thought out, carefully and to the fullest extent.”

Also from Joan Tuppence: Insights and Tips from Local Actors