‘The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse’

Learn from the VMFA exhibition with your mind and your heart

The newest exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts explores and celebrates the culture of African Americans in the South. The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse highlights Black visual art, music, and video, melding the media in a feast for the senses. By transporting the viewer into the African American experience, The Dirty South exhibition at Richmond’s VMFA makes Black joy, tenacity, and sorrow more accessible and understandable.

As a white woman who has been working to learn the fullness of the American experience, I found The Dirty South to be both educational and emotional. The diversity of media and genre in the exhibition and the import of its message encouraged a slow, deliberate perusal of the displays. The background of issues over the past year – and beyond – imbued the message with an even greater meaning.

The name

The moniker “Dirty South” started with Atlanta’s hip-hop music scene. When Atlanta-based rap groups OutKast and Goodie Mob attended an awards show in New York City, they saw their music disrespected by the larger rap world. They determined to earn the respect of the mainstream rappers, and within the next decade, they and other Southern rappers made good on that determination.

Embracing their roots, Southern rappers promoted the Dirty South as a new type of rap music, explained Darren E. Grem, associate professor of history and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi.

Soon, Grem explained, the term became “a loosely defined, inclusive concept and a lucrative set of attractive commodities. … By 2004, the Dirty South was not only a banner under which a wide variety of southern rappers now congregated. It was also a culture industry that had ‘southernized’ what cultural critic Nelson George has termed the multibillion dollar business of ‘hip-hop America.’”

The VMFA exhibition widens that banner further.

“What this exhibition does is speak to the impact of African American visual art and particularly music … on our world today in so many different ways – on the world of art, on the world of pop art, in things commercial,” said Alex Nuerges, VMFA director and CEO.

“My question, and what I tried to answer in this exhibition: What makes Southern hip-hop Southern? What are they drawing upon?” explained Valerie Cassel Oliver, the exhibition’s organizer and the VMFA curator of modern and contemporary art.

The Dirty South exhibition at Richmond’s VMFA encompasses the 1920s to 2020s. It includes more than 140 works of art from 102 artists, including some commissioned art. It offers a wide spectrum of genre, from formally trained artists to folk artists (“intuitive intellectuals” and “vernacular art,” said Oliver of folk art).

“The South is the bedrock. It is the point of origin,” Oliver said, noting that African Americans have their roots in the American South. “[The exhibition] is my love song, if you will, to the South, being a Southerner myself.”

Highlights of The Dirty South exhibition at Richmond’s VMFA

The exhibition divides thematically into landscapes of the South, Black spirituality, and the Black body. Highlights from my visit to the exhibition included:

Soundsuit (Nick Cave, 2010, mixed media including twigs, synthetic berries, metal, and mannequin)

The full-body costume clamored for my attention soon after I entered the exhibition. The costume, approximately eight feet tall, was constructed with hundreds of red-tinged twigs and berries. It arose from the artist and performer’s question after the Rodney King incident in 1992: “How do I exist in a place that sees me as a threat?” A full-body costume can serve as a metaphorical talisman or protective armor – it shields the wearer from bias by totally obscuring race, class, and gender. To add to the intrigue, it can also serve as a musical instrument.

Southern Landscape (Eldzier Cortor, 1941, oil on Masonite)

The 1941 oil painting, by Eldzier Cortor, speaks volumes. A pensive young black woman clutches the cross necklace around her neck. She leans against a stone fence with iron rods for security, a basket of meaningful objects beside her. The larger tale is in the background: land and homes being flooded – probably for “the greater good” – water working its way up to a church and cemetery.

Slugs’ Saloon (Jason Moran, 2018, mixed media – wood, paint, jukebox player, cello, drum set, saw dust, construction hardware, wallpaper, Plexiglass mirror, tin, fabric, vintage outlet cover – and sound)

Imagine the morning after. Imagine the evening before and the life and music that filled the New York East Village jazz saloon. In the reflection, see Revival Meeting (Benny Andrews, 1994, oil and collage on canvas). Nearby – or, if you angle yourself just right and peer into the saloon’s mirrors – is Benny Andrews’ evangelistic “Revival Meeting” (1994, oil and collage on canvas).

From Asterisks in Dockery (Rodney McMillian, 2012, vinyl, thread, wood, paint, lightbulb)

The chapel installation invariably captured my attention, saturated as it was with shades of rich, deep red. The cross in the corner spoke immediately to the room’s purpose and sanctity. But the installation is more than a symbol of a meaningful part of life for many Southern Blacks. It represents an actual historic chapel, Dockery Farm in Mississippi, a former cotton plantation that has been called the “birthplace of the blues.” The red hue can represent blood, power, and conjuring, while the site speaks to to the sanctity of the blues musicians who “worshipped” here.

She Kept Her Conjuring Table Very Neat (Renee Stout, 1990, mixed media)

Although many Africans accepted Christianity after arriving in America, they also brought their West African religious traditions with them. This tidy table, a fictional presentation, pays tribute to traditions that continue to be practiced today.

Art from Sister Gertrude Morgan

Sister Gertrude Morgan represents one of the talented artists who operate in multiple forms: she was a preacher, artist, musician, and poet. The exhibition displays five of her biblically inspired paintings and a decorated paper megaphone that she used in her preaching. Audio of her music, Let’s Make a Record (2005) plays in the background.

Black Corporality, one of the exhibitions themes

As you make your way through this section of the exhibition, hold in your mind the explanatory words of the opening signage, including: “The Black body … holds the cumulative trauma of the South’s painful past that dominates the narrative as well as the significant strains of resistance, resilience, transformation, and joy.”

Let Them Be Children (Deborah Roberts, 2018, acrylic, pastel, ink, and gouache on canvas)

Children – the mental image of children should naturally spark warmth and joy in people of all backgrounds and races. Let yourself feel that natural fondness – and protectiveness for the young as you view this work. Especially in the context of the title, “Let Them Be Children,” this work echoes with pain. The artist “implores viewers to preserve the innocence and sense of well-being of young Black children as they seek to build their own identities while navigating society’s preconceived constructions about their worth in society.” In the art, playfulness is juxtaposed with gestures and expressions of wariness and solemnity, giving attention to the social pressures that the children face. Feel the natural fondness for children, resent the society that robs Black children of their innocence and well-being, and determine to act.

Find out “What’s Booming” in entertainment and other events around Richmond, Virginia

Just Hanging (Felandus Thames, 2014, fat-laced shoestrings, vintage shoes)

Shoestrings are linked in a spiderweb-like structure on an exhibition wall, a pair of shoes dangling below. Think you know what hanging shoes represent? I thought I did, but I was mistaken. The label explains the background of “shoe tossing,” the reality behind the practice, and the stereotypes that have been perpetuated around it. Given the facts, the work represents the understanding of a community’s traditions and its resulting vernacular.

Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death (2016, Arthur Jafa, video installation)

An entire room is devoted to this audio-video presentation. Don’t pass by the powerful message that juxtaposes the conflicting forces and paradoxes of the Black experience in the American South. Stay for the entire 7 minutes and 25 seconds.

Music of the Dirty South

The final room is devoted to Southern Black music. Coming directly after the moving video presentation, it can inspire and educate you. Atlanta hip-hop musicians coined the “Dirty South,” determined to get the respect they deserved. Other musical epicenters arose afterwards: in Houston, Memphis, Miami, New Orleans, and even Hampton Roads. In addition to contemporary artists, interactive displays include talent predating hip-hop.

The Dirty South exhibition at Richmond’s VMFA celebrates Black accomplishments. It acknowledges the challenges without dwelling on them. As a visitor, I came away with a renewed appreciation for the African American experience, for the tenacity required to be Black in America, and for the sheer accomplishment of Black joy.

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse

May 22-Sept. 6, 2021

Including related programs such as speakers, artist talks, film series, and special performances

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

200 N. Arthur Ashe Blvd., Richmond, Virginia

VMFA.museum

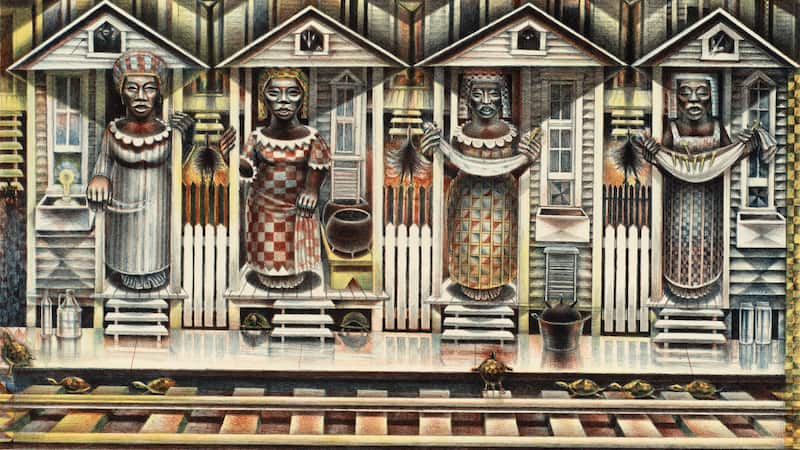

Artwork preceding article:

John Biggers (American, 1924-2001) Four Seasons, 1990 Colored lithograph on paper Gibbes Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, 1994.017 Image: © 2020 John T. Biggers Estate/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Estate Represented by Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, Courtesy of Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association