The Circus World of Tom Robbins

One of America’s favorite and least predictable novelists unveils a much-anticipated memoir

Boomer columnist and author David Robbins wrote this for our print edition in 2014. We are republishing it in 2025 to remember author Tom Robbins, who died on Feb. 9, 2025.

A dozen years ago, when some notable area authors and I took the notion to create a writers’ organization here in Richmond, I volunteered to bring in the keynote speaker for our first big conference.

It would be Tom Robbins.

I had no one second on the list.

Tom is an essentially a native Virginian, born in Blowing Rock, N.C., but growing up in a series of small Tidewater towns – Urbanna, Kilmarnock, Warsaw – and Richmond. He spent so much time here, with extended stops at the Richmond Professional Institute [now Virginia Commonwealth University] and the Times-Dispatch, that we consider him one of our own.

He and I had passed each other briefly along the literary pathways: his Fierce Invalids had beaten my War of the Rats for an award in Chicago, as it should have. I learned later, of course, that he hadn’t noticed.

But I reached out to him through my agent, then his agent. Not long thereafter, at my breakfast, I received a call.

“This is the family black sheep.”

I asked who was calling.

“Cousin Tom.”

And so began what is still one of my favorite friendships. Tom, from his home outside Seattle, and I speak on the phone regularly, though, no, we’re not related. I’ve visited him twice. He’s been to see me twice. I took him and his family sailing. His sister threw up.

THE MAN ACTUALLY IS TOM ROBBINS

At this point, I know Tom Robbins pretty well. For 50 years Robbins, 77, has been an American counterculture iconoclast and icon. His writing has made him famous and wealthy. He’s brilliant. When you read Tom’s work, and you can catch your breath in the circus of language, the aerial fits of philosophy, the nexuses between tin cans and God, you have the inevitable thought:

At this point, I know Tom Robbins pretty well. For 50 years Robbins, 77, has been an American counterculture iconoclast and icon. His writing has made him famous and wealthy. He’s brilliant. When you read Tom’s work, and you can catch your breath in the circus of language, the aerial fits of philosophy, the nexuses between tin cans and God, you have the inevitable thought:

Man, I love this guy’s work. It’s refreshing and buoyant, deep and hilarious, wise and innovative.

Man, I hope this guy’s not a jerk.

The beauty of Tom Robbins is the beauty of Tom Robbins. He the person, not just the writer, is every bit as kind as his books, generous as his ideas, and loyal as our memory of his startling works.

He has almost no ego.

Almost. A few years ago, visiting him, we rode in the car driven by his wife, Alex, who was speeding around a turn through the tulip fields. Tom told her to slow down, that it wasn’t fair to David.

“If we crash, the paper will just say: ‘Tom Robbins Dies With Two Others.’ ”

Tom’s life has been peculiarly American. Humble beginnings, genius asserted at a young age, service in the U.S. Air Force in Korea, college at RPI (now VCU), moved to the West Coast for its liberality, genius asserted again, notoriety, career, dated celebrities, did drugs with celebrities, great career, happiness and now a memoir.

‘THE TRUTH OF LEGENDS’

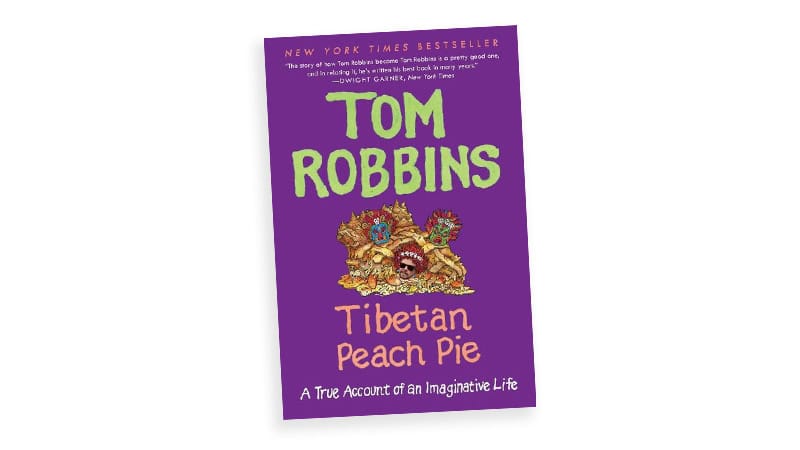

In May, Tom will publish what will likely be his last masterwork, Tibetan Peach Pie: A True Account of an Imaginative Life, from Ecco. He’s struggling with the idea of recording his life for posterity. It’s not in keeping with his Zen way of letting life flow by. He says, “I prefer the truth of legends to the truth of facts.”

When pressed to define what the book is, Tom denies that it’s an autobiography or a memoir. “There are any number of navels I’d prefer to contemplate than my own.”

Then what is it?

“I’ve woven true stories into a resonant narrative.”

A biography or a memoir explains what the author’s life was.

Tom hopes to cast light on what his life means.

“The book is an account of my personal pursuit of the marvelous. It’s candid. But I only embarrass myself.”

He blames the women in his life for pushing him past his reluctance to jot it all down. His wife, trainer, agent, sisters, assistant, all marveled at the stories he told of his careening heydays. One morning when he told his trainer (a circus acrobat) there would be no more, she cried. Tom caved.

“I hate to see a woman cry.”

Tom relates the challenges he encountered in writing a memoir (let’s be honest, it’s a memoir). The first was to sustain his trickery with language when dealing with the real. “Language can happen in a novel. The obstacle in memoir is to keep the language unpredictable when the story is not.”

The other big bugaboo he met and wrestled was, predictably, himself.

“It’s like scuba diving on one’s own life. You’re looking for pearls of great price. But the light is tricky down there. And you have to avoid the tentacles of the giant squid called ego.”

IT’S ABOUT A GIRL, OF COURSE, AND A CIRCUS

I asked Tom for a favorite anecdote out of Tibetan Peach Pie. I could have guessed it would be about the circus, and the time he almost ran away with one.

It happened when he was 9, in a North Carolina summer that moved “as slowly as a celebrity divorce. On a day when lightning kicked its spastic leg.”

On the green in his little town, a great canvas tent was erected. Animals paraded down Main Street. All Tom’s young life he’d read books, escapism from the doldrums of bucolic life. But finally, right in his own town, “I was introduced to otherness, made real.”

As would prove true over the rest of Tom’s life, this story, couched in wonder, was about a girl.

“Bobbi. She wore knee-high boots and a white starched shirt. The eleven year-old daughter of the ringmaster. She had a pet blacksnake wound about her arm. She had little bites where it nibbled on her but she didn’t mind. Bobbi was exotic, a manifestation straight out of the male psyche. She helped me get a job watering the llamas. My parents invited her parents to lunch. It was agreed that I could go with the circus to the next town, forty miles away. Two days later my mom got worried and Dad came and got me.”

Would he have come home on his own? “Never.”

THE GREAT RINGMASTER

Tom is a lifelong adherent of the Japanese aesthetic of wabi sabi, revolving around the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Tibetan Peach Pie promises to be exactly what Tom intends, because what else could it be from his pen? Resonant and wicked, filled with the commonplace made remarkable, cosmic connections built from the ground up to the ineffable. He is a freak and a marvel, and his writings have always surprised. These are the things found in a circus, in wabi sabi and in the tricky light of a life examined, now recorded, by one of the great American ringmasters of language.