My Grandmother’s Treasures

Trinkets of the past open up new worlds and a reverence for family history

“My grandmother’s treasures opened up a world to me and a reverence for my family’s Tennessee history,” writes Boomer reader Julia Nunnally Duncan. She became enamored of the treasures as a child, was granted ownership of many, and went following the story behind one: the military collar disks belonging to a great-uncle.

When I was a child in the 1960s, I liked exploring my grandmother Annie’s house. In her downstairs front room stood an old Remington upright piano that all the grandchildren liked to play; in an upstairs bedroom, military uniforms hung on a clothesline like bodiless soldiers; in the second upstairs bedroom, a bookcase teemed with worn schoolbooks, and a trunk sat in a corner filled with photographs and war medals. On the wall hung a framed oval portrait of my great-grandfather, Dan Lynch, his solemn gaze surveying the scene. Such items seemed like treasures to me, and they fueled my imagination.

Many of my grandmother’s treasures were mementos from her life in Newcomb, Tennessee – a coal mining valley in the Cumberland Mountains, where she was born and raised. Here she married and started a large family, including my father. Her father Dan and two brothers, Condia and Charlie, were coal miners, and all served in the military, her brothers serving in France during World War I.

Beginning her own collection of her grandmother’s treasures

During a period of my childhood, I decided to collect antiques. And where better to start than my grandmother’s house?

“Do you have anything you could give me?” I asked her.

To my delight, she gave me a generous offering: her mother Julia’s gold wedding band; a kitchen gingerbread clock; an aluminum syrup pitcher and two green Ball Mason jars; and an assortment of trinkets – a folding skeleton key, sewing thimbles, a shoe button hook, and two metal buttons.

As I grew into my teens, I learned to read music and played hymns for my grandmother.

One day she said, “When you get married, you can have that piano.” The piano was a player model, its rubber tubing donated during a World War II salvage drive. Though its player mechanisms had been removed, it still played well as a regular piano and retained a Tin Pan Alley sound.

In the mid-1970s, my grandmother passed away, and her house was sold. I inherited the piano and other of my grandmother’s treasures, including the schoolbooks, the portrait of her father, and many of the family photographs from Newcomb. Along with the pictures was a stack of letters my great-grandmother had written to her sons while they were in France, letters that were returned to her undeliverable.

Another like “My Grandmother’s Treasures”: “Apron Strings”

Following the trail of the military insignia

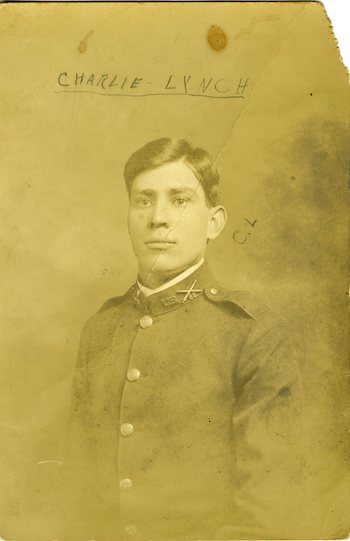

Recently I was looking through the photographs and studying military pictures of my great-uncles Condia and Charlie. I noticed something intriguing in Charlie’s portrait. On his doughboy tunic collar were military insignia – a large U.S. alongside crossed cannons with the number 89 beneath (denoting the 89th Infantry Division and Field Artillery branch). After some research, I realized that the metal buttons my grandmother had once given me, which featured the same insignia that I saw on Charlie’s portrait, had actually been collar disks from Charlie’s uniform. This realization made me more interested in Charlie Lynch—his participation in the Great War and his life afterwards.

Recently I was looking through the photographs and studying military pictures of my great-uncles Condia and Charlie. I noticed something intriguing in Charlie’s portrait. On his doughboy tunic collar were military insignia – a large U.S. alongside crossed cannons with the number 89 beneath (denoting the 89th Infantry Division and Field Artillery branch). After some research, I realized that the metal buttons my grandmother had once given me, which featured the same insignia that I saw on Charlie’s portrait, had actually been collar disks from Charlie’s uniform. This realization made me more interested in Charlie Lynch—his participation in the Great War and his life afterwards.

In my investigations I found that Charlie enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1915. In August 1917, he was transported to France, along with other enlisted men and officers, on the ship Andania, which departed from New York. While in France, he served with the 51st Artillery, Coast Artillery Corps regiment.

In reading one of Julia Lynch’s letters to Condia, dated Nov. 1, 1918, I noticed it included a note written to Condia by his youngest sister, Oma. This note alludes to Charlie and his happy demeanor: “Hope you will get to see brother and hear some of his funny expressions as they say he is in France like he always was at home as jolly as can be.”

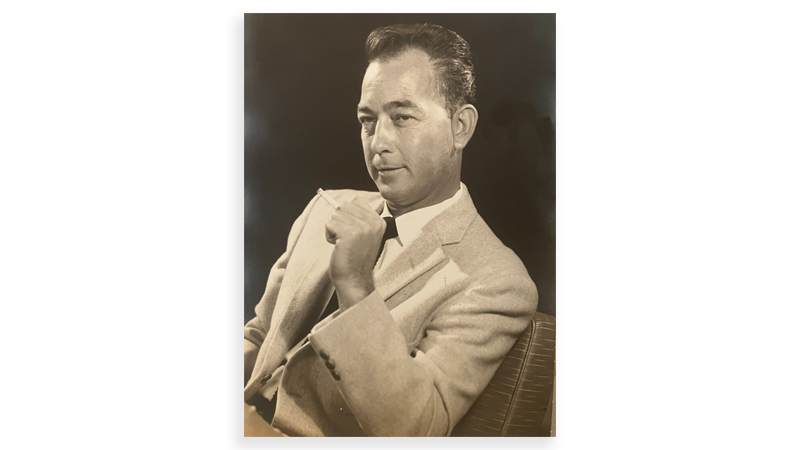

Family stories attest to Charlie’s outgoing manner. My mother recalled meeting him in the 1940s when he was visiting from Tennessee and came to her and my father’s house in Marion, North Carolina. She confirmed that Charlie was extremely friendly. When I asked her if he was still handsome like he was in the military portrait, she said, “No, he was a plain-looking man, tall and slim and kind of bent over when he walked, and he always wore a hat.” She also noted that Charlie had a temper, exhibited by an unexpected outburst at her house. I wondered if the war had affected his personality, which seemed erratic to me, and I wanted to learn more about him.

The 1920 United States Federal Census for Campbell County recorded that Charlie resided in his mother’s household after his discharge from the military in 1920. I also learned that in 1928, he was admitted to a home for disabled volunteer soldiers in Johnson City, Tennessee. In December 1960, just before Christmas, he died and was laid to rest at Mountain Home National Cemetery in Johnson City. Despite my finding these facts about his life, much about him remains a mystery to me – one that I will likely never solve.

Today, I look at the collar disks that my grandmother gave me many years ago, which stimulated an interest in my great-uncle Charlie Lynch. He was a complex man, but one who served honorably in a monumental event and whom I’m proud to call kin. My grandmother’s treasures opened up a world to me and a reverence for my family’s Tennessee history.

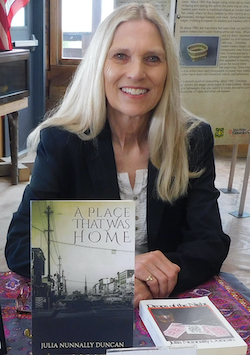

Julia Nunnally Duncan lives in her hometown Marion, North Carolina, where most of her personal essays and poems are set. Her 10 books of prose and poetry include an essay collection, A Place That Was Home (eLectio Publishing), and her essays often appear in Smoky Mountain Living Magazine. Julia is retired now from her profession as an English instructor, but she stays busy writing, gardening, and spending time with her husband, Steve, and their daughter, Annie.

Julia Nunnally Duncan lives in her hometown Marion, North Carolina, where most of her personal essays and poems are set. Her 10 books of prose and poetry include an essay collection, A Place That Was Home (eLectio Publishing), and her essays often appear in Smoky Mountain Living Magazine. Julia is retired now from her profession as an English instructor, but she stays busy writing, gardening, and spending time with her husband, Steve, and their daughter, Annie.

Read more childhood memories from Julia Nunnally Duncan and other contributions from Boomer readers in our From the Reader department.

Have your own childhood memories or other stories you would like to share with our baby boomer audience? View our writers’ guidelines and e-mail our editor at Annie@BoomerMagazine.com with the subject line “‘From Our Readers’ inquiry.”