Eleven Twenty-Two

Childhood memories of the Kennedy assassination

Many people recall where they were and what they were doing on Nov. 22, 1963, when they heard the news that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. Boomer reader Larry P. Lefkowitz shares his memories of the Kennedy assassination and the feelings he experienced as a child.

I was 11 years old in 1963 and I admittedly did not know much about everything. My family was apolitical, possibly because my father was Republican, while my mother was Democrat. Political discussions tended to be brief and incendiary, and thus avoided most of the time.

I went to the school around the corner from where I lived in suburbia, and Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, was an unusually sunny and warm day in our corner of southeastern Pennsylvania. It was an unremarkable day other than the nice weather – we slogged through topics in the classroom while staring out the window and counting the minutes until recess and lunch. My teacher that year was an elderly lady, about five feet tall and mostly calm and pragmatic. Mrs. Lescher seldom raised her voice or lost her composure. She smiled a lot, but never laughed. However, if she pursed her always-lipsticked lips, she scared the daylights out of you.

So it was that on this afternoon, the best that I can recollect 59 years later, we dashed out to the playground after lunch and worked up a sweat playing basketball. After the bell went off to return to the classroom, Mrs. Lescher stood at the front of the class, unsmiling, without lipstick, and started to tell us something in a very stern manner.

Just then, a live news report came blaring over the PA system announcing that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Most of us had no idea what that word meant, but it sounded like vaccinated, so we weren’t shocked until our teacher ran to the wall and began frantically signaling the office to shut the transmission off. We had never seen her like this and most of us became pretty nervous. When the transmission was silenced, she regained her composure and told us the president had been killed. Parents were being summoned to the school to escort us home. At least as many as they could contact. Others were urged to go with friends’ parents. Thus began the long, tragic weekend, whose reverberations would be felt for years, if not forever.

Since my mother was the school crossing guard, I needed only to walk down the sidewalk from the school to see her. She was wearing sunglasses, which was not unusual, but I saw tears running down her cheeks as I approached her. She told me to sit in her car and wait for her to go home. In the meantime, friends passed by – the guys barely looking at me while many of the girls were crying. I was very confused. Apart from a classmate dying the year before in a sledding accident, this was the most profound experience with death I had yet experienced.

When we got home, we watched TV as they broadcast as many gory details as they had. We switched between Walter Cronkite and Huntley-Brinkley, but swelling grief was equally weighty. I didn’t even understand grief.

My mother was fairly stoic, calming friends as they telephoned her to be consoled. She would cry occasionally and briefly, but I think she was mostly dreading my father’s arrival. He would not be home from work for a few hours.

I felt bad in a way I did not understand. It wasn’t like when I got into trouble and angered my parents; it wasn’t like a friend moving away; it wasn’t like going to the doctor; this was a very different feeling. I was missing a person I didn’t even know. What I knew was that this was very wrong and very irreversible. I asked my mother who would take his place and she told me. I deduced this was not good because if my father hated President Kennedy because he was a Democrat, he was going to really hate Lyndon Johnson because he was a Texas Democrat. I didn’t know what that meant either. I was just connecting the dots.

When my father arrived, I heard him say he’d been listening to the assassination coverage on the radio on the way home. He didn’t seem to be grieving, other than feeling helpless that a president of this country could be killed. Looking back on it, my father, a World War II veteran, was probably feeling anger more than sadness, and completely independent of politics. He was a pretty hardened fellow, though, and showing feelings was not in his portfolio of emotions. He was pretty able to get through dinner, though my mother was not, and I was allowed to eat my favorite, peanut butter and jelly on white.

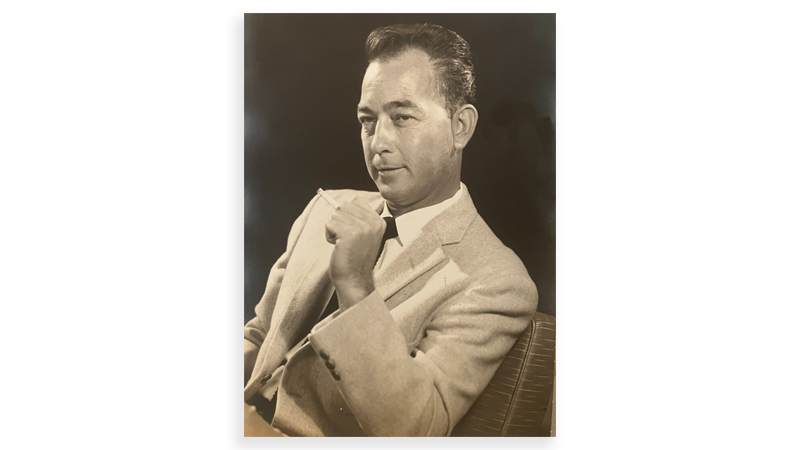

Childhood memories of the Kennedy assassination from David L. Robbins – and later of 9/11

The next day, my mother wanted to watch all of the news coverage, but my father searched in vain to find anything else to watch. Since she wanted the consolation of another human being, she decided to go to my Aunt Bea’s house in Philadelphia.

Of course, I wanted to go because I loved my aunt, but I had to anyway because my mother had no sense of direction and took me along everywhere because I had shown an excellent sense of direction when I was only 6 years old. At 11, I was a walking Rand McNally. So off we went, with bags packed for a few days. My cousin and I became tired and restless late in the afternoon and began nagging our mothers to take us somewhere. We decided to go to the local Chinese restaurant. We turned the TV off and began readying ourselves to walk to the restaurant. Just as we neared the door, the phone rang and Aunt Bea became very excited. She shouted to us to turn the TV back on. Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin, had just been murdered on live TV – the same live TV we had just turned off.

Now I was really confused and lots of questions filled my head. I just remember my mother and my aunt moaning, “Oh no, oh no,” over and over. I didn’t understand why they were distressed that the guy who killed the president had himself been killed. Grief now seemed to edge more closely to fear, especially when it was announced that Oswald had killed a police officer in his escape from the scene. I didn’t know enough to be scared, but I knew enough to feel insecure about everything that was happening. Was the country in danger? Were the people of the country in danger? Were we personally in danger?

The next 24 hours were very sad. We finally went home and my father had found something to watch on TV, but something felt different. No, everything felt different. I had no idea when we would return to school, or when my parents would return to work. I could not imagine what school would be like, especially so close to Thanksgiving and Christmas. These things would sort themselves out over the next few days and months. With the benefit of hindsight, albeit with a colored retrospective, the country had lost its innocence that day. Life as we knew it would never be as protected, free, or benign as it was on Nov. 21. Those who experienced the tragedy would be scarred for life in some way, and our perspective of all things American would be changed forever more.

Larry P. Lefkowitz is a retired technical writer/editor who now teaches classes of other retirees at a local university. He also hosts a music program on an internet radio station.