‘The Crying Indian’

Just who was Iron Eyes Cody?

“The Crying Indian” wasn’t who we thought he was, though that didn’t dilute the environmental message he spread to millions of people. Just who was Iron Eyes Cody?

It might just be the best remembered commercial in television history. Dubbed “The Crying Indian,” the minute-long public service announcement opens with an actor in Native American clothes paddling his canoe. He moves through water that at first appears peaceful and pristine but turns increasingly polluted along the way.

He hauls his canoe onto a plastic-infested shore. The actor looks dejectedly around at the polluted landscape. As he does, a car passing by on a crowded freeway hurls a bag out the window. The bag explodes on the ground at his feet, scattering trash on his moccasins.

A deep-voiced narrator explains: “Some people have a deep, abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. And some people don’t. People start pollution. People can stop it.” The camera pans to one side of the actor’s cheerless face. The actor then turns his face slightly, revealing a single tear slowly coursing down his cheek.

The anti-littering commercial for Keep America Beautiful debuted on Earth Day 1971. It was an immediate success, motivating a frenzy of nationwide efforts which reduced litter by 88% in 38 states.

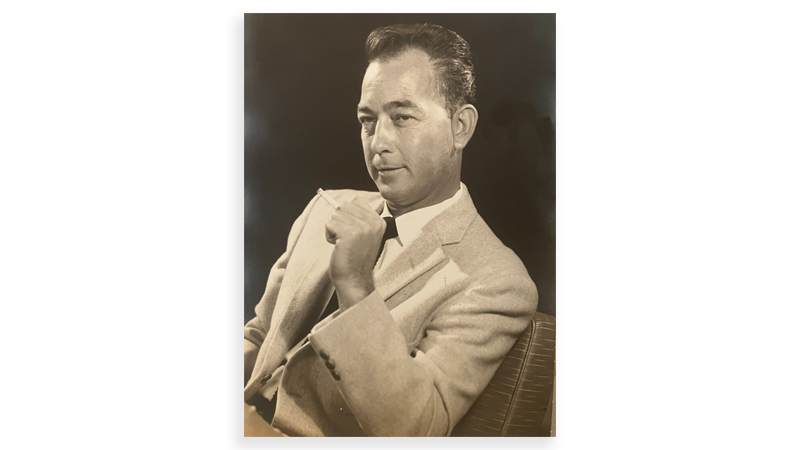

The impact on the actor, a man named Iron Eyes Cody, was extraordinary. He became the public face of Native Americans, honored with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard. Ironically, Iron Eyes Cody had at first resisted doing the commercial because, as he insisted, ‘‘Indians don’t cry.’’ He was convinced to do the commercial by Lady Bird Johnson. One version of the commercial was filmed with the tear and one was filmed without; the version with the tear went on the air.

It’s estimated that Iron Eyes Cody’s face on magazine advertisements, billboards, and posters – in addition to the legendary TV commercial – has been seen more than 14 billion times. He was by far the most recognizable Native American of the 20th century. There was just one massive problem: the man who called himself Iron Eyes Cody was a second-generation Italian without a drop of Native American blood.

Were episodes of “Bewitched” reused and recycled?

Iron Eyes Cody was born Oscar de Corti on April 3, 1904 in Vermillion Parish, Louisiana, to Italian immigrants Antonio de Corti and Francesca Selpietra. Oscar’s mother was from a family of Sicilian winegrowers. She immigrated to Louisiana to work in the sugar cane fields, where immigrant labor had replaced black slave labor. Hers was an arranged marriage.

When Oscar was five his father ran into trouble with the Black Hand, an Italian criminal organization. He fled to Texas, leaving Oscar’s mother struggling to support Oscar, his two brothers and their sister.

In the 1920s Cody’s father left Texas for Hollywood to work as a technical adviser for the movies. He brought his sons along. Oscar quickly got into show business. For a while he toured with a wild west show. When Oscar returned to Los Angeles he started acting in western movies.

About this time, he christened himself Iron Eyes Cody. Why? Why did Oscar de Corti adopt his Native American persona as Iron Eyes Cody?

Maybe he sought to escape the memories of his impoverished Louisiana childhood. Even as a child he had enjoyed dressing up as an Indian.

Or maybe he felt that it made him more employable in the westerns-centric movie industry. He claimed his father was Cherokee and his mother was from the Cree tribe. He also claimed to be from Oklahoma and that he’d been named at birth “Little Eagle.”

Whatever the explanation for his fraud, Oscar de Conti created his own Native American identity. Acting under his new name of Iron Eyes Cody, he stayed remarkably busy for decades. Starting in 1927, he appeared in 200 movies. He worked with Gary Cooper and John Wayne and alongside Steve McQueen in Nevada Smith. By no means were his talents limited to drama. He appeared with Bob Hope in The Paleface and with Jim Varney in Earnest Goes to Camp. He appeared in 100 television episodes in shows like “Sisco Kid” and “Rawhide.”

Iron Eyes Cody’s on-screen portrayal of Native Americans was so persuasive he was often hired as a consultant to movies and television shows. For producers seeking Native American authenticity, Iron Eyes Cody was Hollywood’s go-to guy. Even off screen he kept up the deception, going around Los Angles wearing beaded moccasins and a buckskin jacket. All this from a man without a drop of Native American blood.

The deceit could not possibly last forever and it didn’t. After all, his two brothers kept their obviously Italian last name. Some real Native Americans in the movie making industry, including Jay Silverheels (the Tonto of Lone Ranger and Tonto fame), inevitably started questioning Iron Eyes’ authenticity. It all came crashing down in 1996.

A reporter from the New Orleans Time-Picayune traveled to Iron Eyes Cody’s hometown. The reporter interviewed the actor’s family and learned that Iron Eyes was not Native American; the man was 100% Italian. Based on an interview with a half-sister, May Abshire, and a review of Holy Rosary Catholic church baptismal records as well as other documentation, the reporter concluded that Mr. Cody was a second-generation Italian American.

But Iron Eyes Cody refused to acknowledge the truth. “You can’t prove it,” he insisted when confronted by the reporter. He never did admit his deception, sticking to his story until he died at 94 in 1996.

The decades-long fakery of Iron Eyes Cody seems rather harmless. No one was hurt by it. And he gave us that truly iconic tear.

John Sullivan is a Baltimore lawyer and writer. His novel about a scam, “Mr. Fox,” is seeking a publisher.

Sources

- “Verdugo Views: The True Story of Iron Eyes Cody,” Glendale News-Press, August 28, 2014.

- “The True Story of ‘The Crying Indian,’” https://proceonomics.com.

- Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images, Finis Dunaway, University of Chicago Press (2015).

- “Iron Eyes Cody, 94, An actor and tearful anti-littering icon,” Amy Waldman, New York Times obituary, January 5, 1989.

- “Iron Eyes Cody – The Crying Indian,” https://valleyrelicsmuseum.org.

- “The Life and Tragic End of Iron Eyes Cody,” www.youtube.com.

- “Native Son,” Angela Aleiss, Times-Picayune, May 26, 1996.

In 2023, Keep America Beautiful transferred rights to the ad to the National Congress of American Indians Fund, the educational arm of the group based in Washington, which retired the ad, saying it was “inappropriate” then and now and restricted its use to settings where it can be understood within a “historical context.” From the New York Times