A Tale of Two Heroes

A POW and the wife who rose to the challenge of bringing him home

Listen to Part 1:

Listen to Part 2:

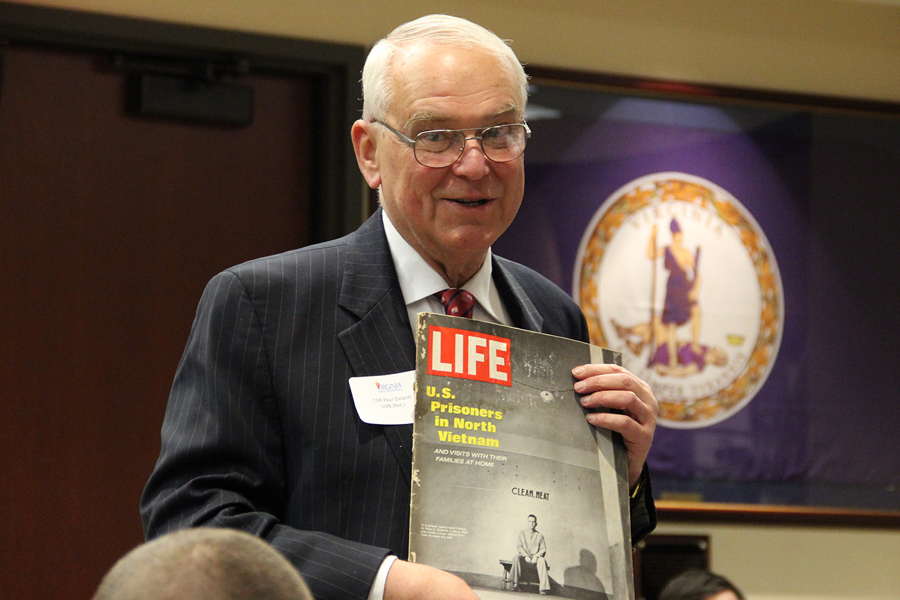

When serving as a U.S. Navy pilot during the Vietnam War, Paul E. Galanti was shot down and captured. His wife, Phyllis, became a fierce advocate for the return of the Americans held as prisoners. After his retirement with the rank of lieutenant commander, Paul Galanti held several non-military positions and served as commissioner of the Virginia Department of Veterans Services. The Galantis have been honored for their service.

Bill Bevins recently sat down to talk with Paul Galanti for Richmond’s Star 100.9 Bill and Shelly radio show.

“He was a hero to a lot of us who grew up in the Richmond area during the Vietnam War,” said Bill Bevins. “We wore POW bracelets, and Paul Galanti’s name was on a lot of kids in my high school. If you look up the definition of ‘hero,’ if you don’t find Paul Galanti, you need to check your reference book.”

Bill Bevins: We are so honored to have Paul E. Galanti in the studio today. Good morning, sir.

Paul Galanti: Good morning, Bill.

BB: Your honors from the military include a Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, Bronze Star, nine combat Air Medals and two Purple Hearts. You grew up in a military family, didn’t you?

PG: I did. My dad was a career Army officer.

BB: Did you want to be a flyer almost from day one?

PG: I knew what a P-38 was before I could count to 38, a P-24 before I could count to 24. I grew up on air bases. Fourth grade, [an airshow] at Fort Levenworth, Kansas, was the first time I saw a jet fighter, a YP-80 Shooting Star flown by Capt. Chuck Yeager.

BB: Oh, my gosh! So you were hooked?

PG: I was. I saw that airplane go at over 200, 300, 400 and 500 miles per hour, and I knew what I wanted to do.

BB: Let’s jump ahead. Vietnam comes along and you were flying what kind of plane?

PG: The A-4 Skyhawk, off a World War II carrier. I flew 97 missions – some super hairy, some of them not so bad.

BB: You were shot down over Vietnam and taken prisoner when?

PG: June 17, 1966. I call it my joining the Hanoi skydiving club.

BB: When you got to the infamous prison, Hanoi Hilton, you had somebody pretty famous held with you, is that correct?

PG: Several turned famous and one ended up being a presidential candidate, U.S. congressman and senator from Arizona.

BB: John McCain.

PG: Yeah, John McCain. Good guy. He used to be our clown.

BB: When he ran for president, his sense of humor showed.

PG: [The Navy] really was a good bunch of people. Our first class at Pensacola, someone told us, “One of the three of you is not going to be around in five years,” and that’s about what the fatality rate was. It was pretty dangerous. If you have a single-engine airplane and a bullet goes into the engine, there’s not a whole lot of luck involved with that.

BB: You’re being held prisoner of war at what you’ve called “a gated community” with how many folks?

PG: I was number 87 shot down and captured there, so probably 87 or 88. They threw me in a cell and didn’t do anything for three days. I was starving and thirsty [and eventually] ended up in interrogation. This was the first time I had ever been tortured and beaten.

BB: Was it a regular thing to be tortured?

PG: It wasn’t regular. Nobody got tortured every day except when you’re in interrogation and refuse to do stuff. [Training] can’t prepare somebody for that. The worst thing is not knowing when it’s going to be over.

BB: How did you not lose your mind?

PG: I’m not saying I didn’t lose it. It was really rough. Solitary confinement was the worst for me. The beatings were bad, but they can only do that for so long. You either passed out or they had to quit, but the solitary confinement, not knowing when that was going to end day after day. We could tap on the walls, some communication with other Americans – it wasn’t much, but it was a little bit. You still felt like you were climbing the walls sometimes. You wanted to get away but you couldn’t; you were stuck in this little seven-by-seven-foot cell. We didn’t have any air conditioning or heat, either. Summertime, it was probably 125 or 130 degrees. In the wintertime, it went down to the 30s or low 40s.

BB: You were held for how many years?

PG: Six years and eight months.

BB: You know the days, too.

PG: 2,438 days.

BB: I had the great honor of meeting your beautiful bride, Phyllis Galanti. Tell us a little about her.

BB: I had the great honor of meeting your beautiful bride, Phyllis Galanti. Tell us a little about her.

PG: Both of our fathers were career Army officers. We dated off and on for the four years I was a midshipman and got married while I was still in flight training.

BB: I want to jump ahead. You’re being held prisoner of war and I know you were worried about her and all that she was going through. It turns out when you got back home that this sweet girl was one heck of a fighter. She was on TV, doing radio interviews, in the paper. She was making sure that nobody forgot about the prisoners of war.

PG: She did what Navy wives are supposed to, [being] nice and quiet, for a couple years. The wives decided after a while, “This stinks. They’ve been over there longer than World War II and we’ve got to do something.” They formed the National League of [POW/MIA] Families. Admiral [Vice Admiral James] Stockdale’s wife, Sybil, asked Phyllis to fill in for her at some of the congressional hearings. At one point, Phyllis called Ross Perot, who had run an awareness program in Dallas. “Phyllis, you go down and get every business leader in Richmond, university presidents, bank presidents, all in one big room and I want to talk to them.” He flew in and Phyllis ended up having the most successful letter-writing campaign in history. Every school kid was writing letters. The thing was “Bring Paul Home.” Nobody knew who the heck Paul was, but they were writing letters to bring him home. I can’t tell you how many people came up to me after I came home and said, “That little lady of yours is doing a heck of a job!”

BB: She was an amazing woman. The Virginia War Memorial honored you and her with a special honor.

PG: Dr. Bruce Heilman, on the board for the War Memorial, and [Rear Admiral John] Hekman, executive director, [told Phyllis and me], “We want to name the new education center after you two.”

[At the groundbreaking ceremony] on Dec. 17, 2010, [I said to Gov. Tim Kaine], “I just want you to know, sir, that if my old chemistry prof at Navy knew that they were naming a building with the words ‘Galanti’ and ‘education’ in the same title, he’d do aileron rolls in his grave.”

BB: [laughs] McGuire Center named the arboretum after your wife.

PG: That’s really touching because she was really into things green. I think there are two reasons [for improvement in POW treatment] – one is the stuff that Phyllis and Sybil Stockdale and a few of the wives did to get [the North Vietnamese] bad publicity, which Communists hate. And they released a couple of prisoners early – [one] came home and started blowing the whistle, so the public was outraged.

BB: A lot of that was due to Phyllis Galanti and the other wives.

PG: It was.

BB: Give everybody a patriotic thought to close with.

PG: Three things I learned: the first was, I wasn’t as tough as I thought was. I learned that no matter how bad I had it, somebody else always had it worse. But the most important thing I learned came from solitary confinement – there’s no such thing as a bad day when there’s a door knob on the inside of the door.