Gretchen’s Handkerchief

Remembering a childhood piano teacher and her old-fashioned ways

The meaning of some items reach deeper than their superficial use. Such was the case for a handkerchief, always in the possession of a genteel piano teacher named Gretchen. Boomer reader Julia Nunnally Duncan remembers her teacher and the dainty cloth accessory.

In the mid-1970s, my piano teacher, Gretchen, wore a prim skirt and silky white blouse with a high ruffle collar and long sleeves. Her dark hair was amassed on top of her head in Gibson Girl style, and in her sleeve cuff she tucked a lacy white handkerchief. She gave lessons at the First Baptist and First Methodist churches in Old Fort, a township in McDowell County, and for a while she came to my home in Marion to teach me.

A woman in her 50s, she was the daughter of Southern Baptist missionaries and a missionary herself. She and her minister husband lived in Ridgecrest in neighboring Buncombe County, near the Montreat home of evangelist Billy Graham. She called me “Sister,” in a churchy way, saying things like “Lighten your touch, Sister,” as I pounded out a Beethoven sonata.

She took her music instruction as seriously as her religion. She had been a music teacher in the McDowell County public school system, and I met her in 1969 at Pleasant Gardens School, where she was my junior high school glee club director. Later, as my piano teacher, she introduced me to scales and finger dexterity, emphasizing memorization, public performance, and statewide competition. She was a patient and accomplished teacher.

I thought it odd, though, the old-fashioned way she dressed. When I settled on the piano bench, she in a chair beside me, I felt a little self-conscious in my patched blue jeans. Gretchen reminded me of the proper older ladies from my childhood Baptist church, whose presence demanded respect.

What puzzled me most, though, was Gretchen’s frilly handkerchief. I had never seen anyone carry a handkerchief in her sleeve like Gretchen did. I had seen such handkerchiefs in decorative gift boxes at our local Roses five and dime in the 1960s, and my mother and I found a couple of these handkerchief gift sets in my paternal grandmother’s bedroom drawer after she died in 1975. One box held two white handkerchiefs embellished with colorful embroidered flowers. The other, which featured little green shamrock stickers proclaiming “ALL IRISH LINEN,” held two white handkerchiefs bordered with lace.

“These were never opened,” I told my mother as I studied the boxes. Though unopened, the boxes showed the wear of time, the cardboard warped and the plastic lids slightly discolored. A mildew spot had made its way to one of the handkerchiefs.

“These were never opened,” I told my mother as I studied the boxes. Though unopened, the boxes showed the wear of time, the cardboard warped and the plastic lids slightly discolored. A mildew spot had made its way to one of the handkerchiefs.

In the drawer were also stored some loose handkerchiefs with floral designs. These individual handkerchiefs were neatly folded and also seemingly unused.

Since no one else in the family seemed interested in the handkerchiefs, my mother asked if she might have them. For years she kept the two boxed sets and loose handkerchiefs stored in a bedroom drawer and later passed them on to me. I keep them in a bedroom drawer, the boxes undisturbed. I have used the loose handkerchiefs, however, placing them in my curio cabinet as scarves under my music boxes. These scalloped, floral-patterned scarves add a Victorian touch to the room and remind me of my grandmother.

Ladies’ handkerchiefs of this sort might be a thing of the past. I don’t recall my mother ever carrying a handkerchief, and certainly I’ve never carried one. Kleenex tissues serve my purpose, and I generally have one of these stuffed in my jeans or jacket pocket. I have read, though, that there was a time when ladies customarily carried a handkerchief in a purse or tucked in their bosom or sleeve. In the Victorian era, a lady might have dropped a handkerchief to discreetly attract a man’s attention. But the flu epidemic of 1918 [an aggressive ad campaign from Kleenex touting their new paper tissues] put a curb on the use of cloth handkerchiefs as people feared harboring germs in their clothes.

Despite this custom having been mostly deserted in the early 20th century, dainty ladies’ handkerchiefs were still available at our Roses five-and-dime in the 1960s, and my piano teacher, Gretchen, still tucked one in her blouse sleeve in the 1970s. I imagine Gretchen’s handkerchief might have been lightly scented with perfume. Though her old-fashioned manner seemed peculiar to the teenager I was then, she was a memorable teacher and a reminder of more genteel times.

Julia Nunnally Duncan lives in her hometown of Marion, North Carolina, where most of her personal essays and poems are set. Her 10 books of prose and poetry include an essay collection, A Place That Was Home (eLectio Publishing), and her essays often appear in Smoky Mountain Living Magazine.

Julia Nunnally Duncan lives in her hometown of Marion, North Carolina, where most of her personal essays and poems are set. Her 10 books of prose and poetry include an essay collection, A Place That Was Home (eLectio Publishing), and her essays often appear in Smoky Mountain Living Magazine.

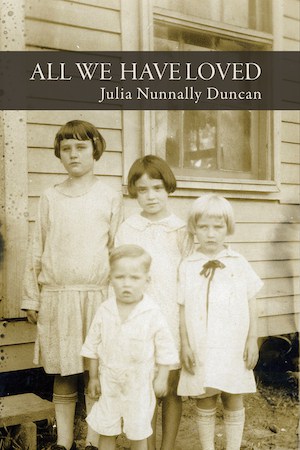

Duncan’s most recent book, All We Have Loved, is an intimate portrait of a woman’s life in Western North Carolina, a place of unique culture and traditions. The book is filled with items, like the handkerchief, that capture the moments of life: ominous and violent or loving and joyful. All We Have Loved explores universal themes of family love, attachment to a place, and the enduring power of friendship. Readers can order her book online at Finishing Line Press.

Julia is retired now from her profession as an English instructor, but she stays busy writing, gardening, and spending time with her husband, Steve, and their daughter, Annie.

What’s old is new again: Substituting reusable for single-use products saves money and the Earth

Read more childhood memories and other contributions from Boomer readers in our From the Reader department.

Have your own childhood memories or other stories you’d like to share with our baby boomer audience? View our writers’ guidelines and e-mail our editor at Annie@BoomerMagazine.com with the subject line “‘From Our Readers’ inquiry.”