Making It Easier to Get Around the Richmond Area

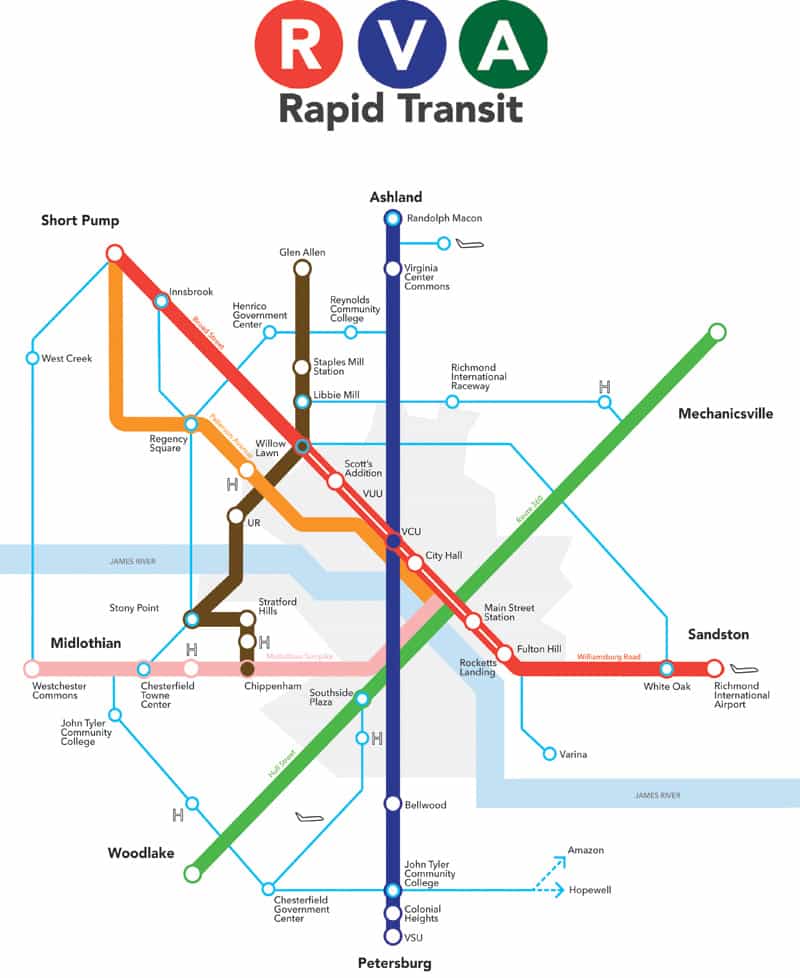

Greater RVA Transit Vision Plan

Imagine being able to walk to the end of your neighborhood – even if it’s several miles from the city center – to take mass transit anywhere in town, for shopping and entertainment, to attend community meetings or to visit with friends. With high-quality rapid transit coming to the Richmond area within 10 years, this dream may become a reality.

Imagine being able to walk to the end of your neighborhood – even if it’s several miles from the city center – to take mass transit anywhere in town, for shopping and entertainment, to attend community meetings or to visit with friends. With high-quality rapid transit coming to the Richmond area within 10 years, this dream may become a reality.

The details are in the Greater RVA Transit Vision Plan adopted by the Metropolitan Richmond Transportation Planning Organization on April 6. The plan calls for Rapid Transit on RVA’s four main corridors – routes 1, 60, 250 and 360 – with neighborhood, employer and cross-county connections throughout. From Ashland to Petersburg, Woodlake to Mechanicsville, Short Pump to the airport, and Midlothian to Main Street Station, the system will run at 10- to 15-minute intervals, seven days a week, at least 16 hours a day.

Now the plan goes to county and city authorities for feasibility study and implementation. Richmond Metropolitan Transit Authority (RMTA) has been empowered by Virginia’s General Assembly to operate the system, if they desire.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is the backbone of the plan. BRT brings most of the advantages of high-cost light rail and subways to a midsize city like RVA at a fraction of the cost.

BRT will run along an existing roadway (a big cost-saver since it doesn’t require breaking new ground), setting aside dedicated lanes for speed and safety. Stations will be located at major activity centers. Passengers purchase fares from a kiosk and board the BRT on a platform level with the bus, with a gap small enough to allow wheeling a suitcase, wheelchair or stroller across. The vehicles travel 30 percent faster than conventional buses in center cities and at speeds as high as 50 mph in suburban areas. There’s even Wi-Fi on board.

RVA’s rapid transit system was relatively easy to design since most of metro Richmond’s economic centers are clustered around four major corridors. The initial BRT corridors total 115 miles of roadway. The stations will be fed by local buses that cut across town. Small vans will provide door-to-door service to subdivisions, schools and businesses.

Wherever you are in the service area, you will be able to get to a BRT corridor that connects you to the whole metro city.

WHY SHOULD WE CARE?

According to RVA’s Age Wave study, boomers are increasingly interested in having access to efficient rapid transit.

“We boomers defined ourselves by cars and freedom,” explains John Martin, who heads RVA’s Southeastern Institute of Research (SIR). Boomers want to preserve their freedom, “to maintain vitality and mobility.” Having access to transportation could easily determine whether they are able to continue living in their existing homes.

Millennials, on the other hand, define themselves “by community and relationship,” he says, and America’s cities are competing for them. By 2025, they’ll be nearly half the workforce. The cities that attract them will prosper. Millennials are seeking out first, a place where they want to live and second, a job. “They choose cities that have good public transportation.”

For young people and unemployed persons who need a job before they can afford a car, rapid transit is essential. For minimum wage earners, it’s worth about $4,000 a year – a 30 percent boost in income.

So there’s a convergence – a community of interest between boomers and millennials. Boomers want to preserve their freedom, “to maintain vitality and mobility.” Millennials want a place with good public transit.

Great cities have great public transit. Permanent rapid transit – based on a capital investment in corridors and stations – attracts permanent economic development. In America’s 30 largest cities today, as much as 80 percent of new commercial development is within walking distance of public transit stations. Planners call this WalkUp development – Walkable Urban development – walkable residential, business and shopping areas, with parks, bike trails, sidewalk cafés. It takes density to create great urban attractions, such as sports venues, concerts, museums, universities, hospitals and retail. If you have dramatic public transit, you draw those institutions.

Metro Richmond has been slow to develop a rapid transit system, but interest seems to be awakening rapidly. The Pulse, the first piece of RVA’s system, opens on Broad Street this fall. “The RVA brand has become a symbol of what we are becoming,” John Martin says. “We have finally reached the point where we can talk about the future in a positive way.”

Martin does major consulting for cities all over the country, and they want transit. They are saying, “How much more transit can we get?”

Ross Catrow, head of RVA Rapid Transit, says that more than 50 American cities had transit referenda on their ballots last November, and 71 percent of them passed.

How would RVA pay for a 115-mile system? It’s still in the works. If Virginia’s General Assembly gives metro Richmond the same deal they gave Hampton Roads and Northern Virginia several years ago, authorities could build and operate the system by raising the sales tax from 5.3 to 6 percent.

With the RVA Transit Vision Plan, one-quarter of the work is already done. Chesterfield and Henrico are beginning feasibility studies based on the study. Five years from the time that the supervisors of Chesterfield, Hanover, Henrico and Richmond decide they want to proceed, the full system could be built. RVA could potentially move from its current position of 92nd in public mobility among U.S. cities to one of the top 10.

Just like that.

The Rev. Ben Campbell is pastoral associate at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and a board member of RVA Rapid Transit, RVARapidTransit.org, which advocates for a regional public transportation system.