The Heart Remembers

Dusty childhood memories

Boomer reader Michael W. Updike recalls dusty memories of his youth, humble people who touched his soul. Today, childhood memories stir the heart still, sparked by sights and smells.

My heart remembers Mrs. Groves and her tiny green asbestos-shingled Sears-Roebuck catalog house directly beside the City Point National Cemetery in my little rusty, dusty childhood community.

My parents interacted with her quite a bit, sharing vegetables and fresh-caught fish and fixing things that broke around the 85+ year-old lady’s property.

I never knew a Mr. Groves, but I’m sure there had to be one at some time.

Mrs. Groves walked by our house and around the neighborhood nearly every day. She would stop and talk, sometimes coming into our house, but mostly just talking through the porch screen to my parents and us boys. My dad even taught the old but spry octogenarian to fly fish, like he had me and my brother, but that’s another story for another day.

One snowy Christmas Eve, the black rotary dial phone rang; Mrs. Groves’ pot-bellied stove had gone out and she couldn’t get it relit. She was freezing, so my dad and I – 8 years old and always happy to go somewhere with him, especially in the snow – grabbed a couple of tools and set out into the night to fix her stove.

A flame is sparked

Here’s where the psychological phenomenon began.

I followed Dad through the front door into the living room and the scene was set forever in the concrete-gray recesses of my mind, or my heart.

It was like I had stepped into a vacuum; a Twilight Zone of silence, isolation … and sadness.

Surrounded by stark, dark, and woodsmoke-stained walls, wrapped in an ancient hand-knitted and tattered Afghan blanket, coarse whitish-gray hair and age-spotted skin wrinkles escaping the clutches of a crocheted Scottish-looking bonnet with a dirty, dull, formerly pink ball on top, Mrs. Groves apologized for summoning Dad out into the snow and cold.

There was nothing but age and peeling paint and roof-leak-stained wallpaper on the walls; no furniture save the stove and a straight-back chair on loan from the kitchen table; no five-and-dime paintings, no Christmas tree, no cheap souvenirs from some long-closed attraction. Nothing, and to my innocent and naive eyes, maybe even less than nothing.

The imagery etched itself into my heart and into some of my songs, most notably “Someone Else’s Christmas.” which received some airplay and positive attention but was a little lengthy to break into holiday rotation on the radio.

Well, Dad found that rain and melted snow had come down the stovepipe and waterlogged everything inside the stove. We cleaned out the water-soaked wood and ashes and brought dry wood in the house. In less than an hour, we had Mrs. Groves warm and dry, even if she was still lonely as a castaway.

The heart remembers what the mind forgets

Since living that bleak scene in real-time as a youngster, I have relived that barren setting dozens of times – up in Aunt Reba’s grubby, four-foot-high ceilinged garret with wall-to-wall dusty, sheetless, and stained tick of cotton lump mattresses. We slept as soundly as Rip Van Winkle in this sparse space when we’d visit the “mountains” of Bedford, Virginia – my dad’s childhood stomping grounds.

Out on the splintered rough-hewn wood porch, Uncle Mike, face disfigured from an adolescent suicide attempt, played his old Gibson banjo in a scene not so different from the Deliverance banjo boy act in the movie.

Somewhere, in my subconscious heart, I recognized the energy and beauty of the music amid the horror and grotesqueness of the damage done in a moment of youthful misguidedness.

I re-experienced that same desolation and self-imposed solitude with Mr. Vincent and his gutted-out, huge former plantation home on the road to the Historic Triangle of Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown. Bare earth was visible beneath the missing floor planks of the 18th-century home. Even at 12 years young, I could sense the old fellow’s embarrassment over the state of the once-great manor when we came to visit.

My dad had befriended the aged, one-armed farmer, and we would bring him food and drink on Dad’s days off. I’m sure he felt some kind of kinship with Mr. Vincent, given their shared farming and backcountry upbringings.

We were likely his only human visitors for months on end, excepting the occasional traveler wanting to buy one of his rusty, antique farming implements to become yard ornaments in their well-groomed McMansions in Sweet Living Estates.

Mr. Vincent would just respond, “If I sell you that plow [or harrow or tedder], how will I work my land?”

He seldom spoke of a wife or children, though he once mentioned his daughters had graduated from William and Mary College at some time in the past. His family showed up to claim the property upon his passing, but never came around while he was alive, that I was aware of.

They turned it into a handsome and stately B&B replete with an English garden and equestrian facilities.

From all outward appearances, desolation dominated his dirt-row days and heartbreak haunted his never-ending nights until his death in the 1980s.

Life-saving, soul-touching memories

I felt that same eerie emptiness, déjà blue and hazy gray, when I saw Mr. Vincent’s ghost driving his 1919 Fordson tractor right down the middle of the misty byway during one beer-addled and smoke-obscured 3 a.m. trip home from the beach when I was in my 20s.

I was running nearly twice what the speed limit allowed into a 45-mph turn when I encountered Mr. Vincent straddling the center line, one-armed and wearily slouching, his dirty planter’s hat pulled down so far it curled his sun-scorched ears outward like the absurdly short wings of a cartoon airplane.

I jerked the wheel too hard left, then too hard right. My spanking-new Bronco spit gravel from both road shoulders of that crisscross curve, then settled, right and proper, in my lawful lane just in time for me to nod to the Virginia state trooper coming from the opposite direction and totally unaware of my misdeed – or of Mr. Vincent’s ghost. That miracle maneuver would never have happened except for the conniving of the Coors … and the hand of God.

“Just Flowers: Memories of My Mother,” by Michael W. Updike

My heart recalls scenes of my life all the way back to the ocean water coming in under the door of our beachfront bungalow in Cocoa Beach, our home base as Dad helped build the Mercury launch pads at Cape Canaveral.

Mom put towels under the door bottom to stop the hurricane’s tidal surge out of our house. The towels could not abate the palmetto bugs, though. And apart from those high-brow Florida roaches, Fiji had nothing on this tropical paradise in the early 1970s.

Though I was only 2 or 3 years old, I have vivid memories of the blue lights of Daytona as we traveled the famed U.S. Route 1 in the midnight hours of our many journeys to and from the Sunshine State as my Dad sought employment.

The good Lord gives us senses of hearing, taste, touch, smell, and sight; some would say there are other senses provided to us.

To me, smell and sight bring back the most vivid memories.

I have often wondered how, exactly, the brain works in tandem with a sense, such as smell or sight, to broadcast a barrage of sadness and sorrow or happiness and joy through the entire body-soul network.

Sometimes these floods can consume a person to the point of emotional collapse or, at the other end of the spectrum, cause emotions to soar to the heights. We have all felt this to one degree or another at some time in our lives.

Maybe it was not the mind at all; maybe it was that mysterious, thoroughly misunderstood organ, whether physical or spiritual, known as the “heart.”

The heart remembers what the mind forgets.

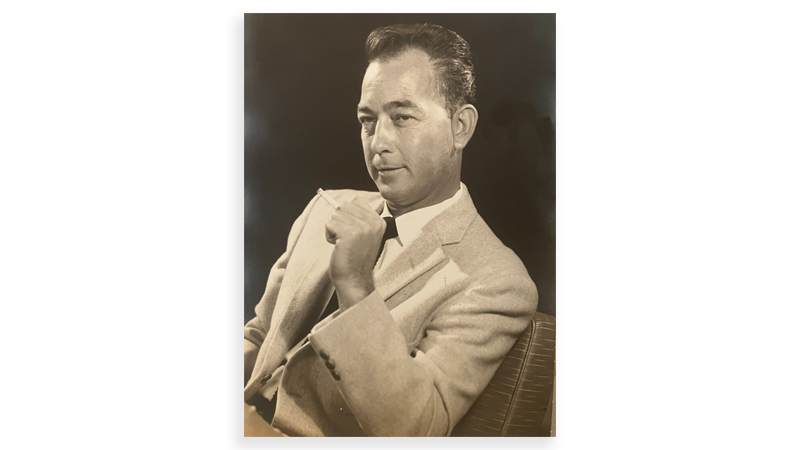

Michael W. Updike is a singer, songwriter and author. He lives in a 1930s Virginia plantation-country farmhouse, which he renovated. Michael also collects and restores antique cars. He enjoys spending time with the love of his life, Jennifer, and their family.