Bringing Hidden African-American History to Light

A Library of Virginia digital project brings unknown stories to the surface.

A free black woman who relocated from Accomack County to New York travels to Georgia with a new employer, who asks her to pretend to be enslaved for her safety. Once in Virginia, she’s sold to slave traders.

This and other previously unknown stories on the lives of African-American Virginians before the Civil War can be learned through a groundbreaking Library of Virginia digital project.

Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative offers a new online collection of local, primary-source records documenting the experiences of enslaved and freed black people as far back as the 17th century.

“It’s groundbreaking because this work is bringing into the available history names and something of the lives of people who were not in the history books,” says Nat Wooding of Chesterfield County, one of the citizen historians transcribing the documents.

A MASSIVE UNDERTAKING

Started in 2013, the project has indexed 100,000 African-American names and created nearly 40,000 digital images. So far, images of nearly 6,000 records were transcribed through crowdsourcing to provide greater search capability and promote understanding and conversation about African-American history.

Wooding, a semi-retired biologist and history aficionado, has transcribed 800 pages and proofread and approved another 900 pages of work completed by others. Different types of documents he has transcribed and edited include freedom lawsuits filed by the enslaved, which were sometimes successful; registration papers, which were required for free blacks; and coroner’s inquests that “read like a prehistoric CSI script,” he says.

“Life hasn’t changed very much in terms of what people do to one another or to themselves. There were drownings, deaths from exposure, murders, natural deaths and girls hiding a pregnancy and then abandoning the baby. Of course, unless there were obvious signs of trauma and a doctor did not examine the corpse, there was not much that the jury could say other than ‘death by visitation of God.’”

Transcribing the handwritten documents improves the search capacity of the vast collection of records by allowing for full-text keyword searching. Transcribers zoom in on a scan of the original document and type the words into a text box.

The public is invited to transcribe. Transcribe sessions are held at the Library of Virginia the last Saturday of each month. Volunteers are on hand to assist new transcribers.

“There is a whole lot of information, which has been tied up literally because these documents often come together in bundles tied with a ribbon and stuck in boxes buried in courthouses or archives, and access to them is difficult,” Wooding says. “Now somebody anywhere in the world with access to the internet can read these things. There are novels and screenplays galore.”

REVEALING STORIES

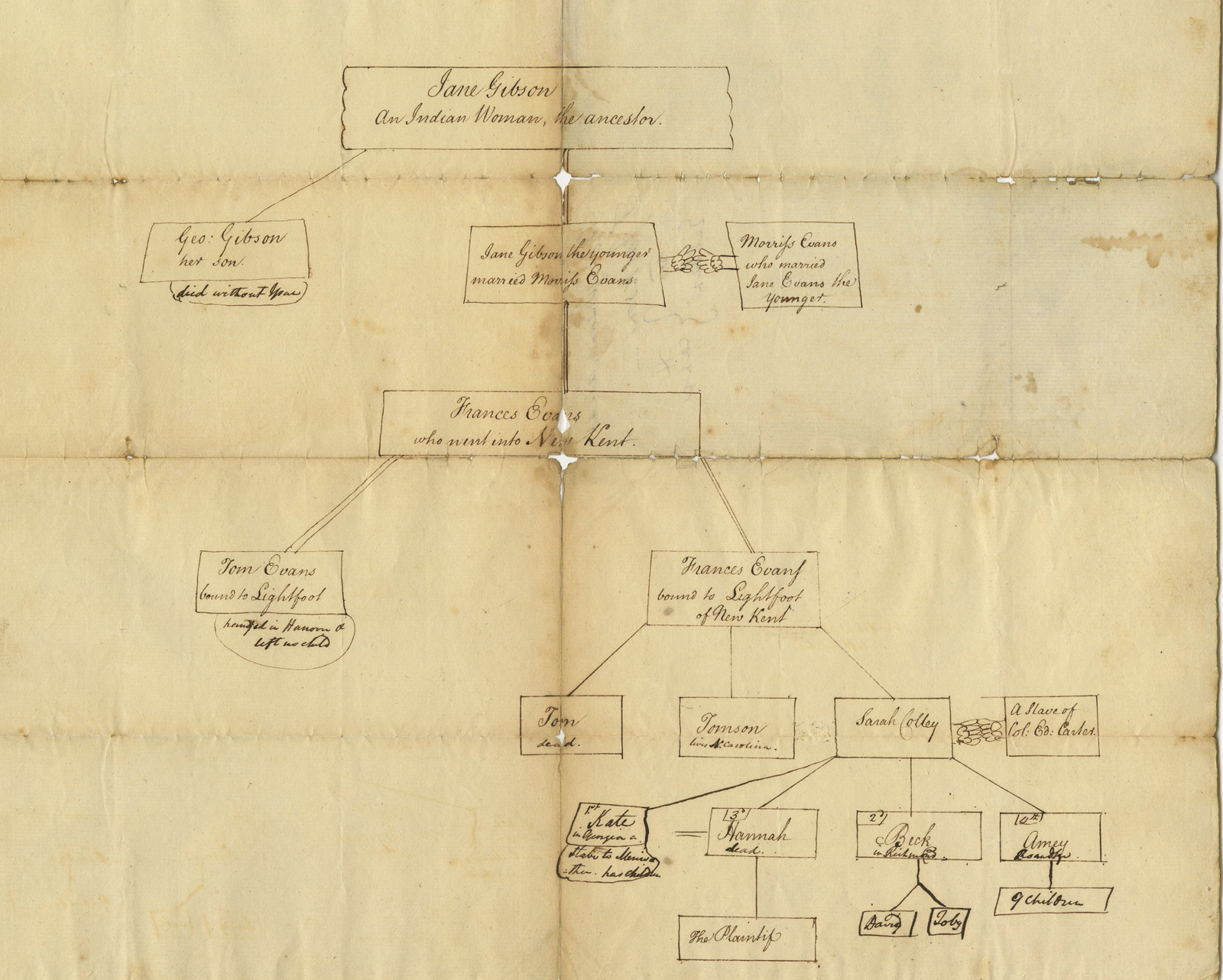

The project reveals a fuller narrative about African-American experiences during an era that looms like a brick wall for researchers because there is so little information available, says Greg Crawford, local records program manager and the driving force behind the project. “What we are trying to do is knock holes through that wall to give people more access to African-American history and genealogy. A lot of the records are local court records that were stored around the commonwealth and in library basements, and they have been relatively untouched for several centuries. We’ve been able to gain access to these records in drawers and attics. We have identified African-American history and genealogy that has been untapped for a couple of centuries.”

Local court records provide a strong sense of what was happening in a county at that time and, unlike a textbook, the documents are firsthand accounts, often by the individuals.

When Crawford does a presentation, he says, “The first image I show is a drawer full of bundled records from the 1800s and (I say,) inside those bundles are stories of individuals who are saying, ‘Tell my story, tell my account.’ ”

One compelling story involved Hester Jane Carr, an African-American woman who was born free in Accomack County. She relocated to New York City to work as a housekeeper. While there, she met a new employer who wanted Hester to work as a “waiting maid” for her in Columbus, Georgia. For safe passage into Virginia, Hester was told to pretend she was her employer’s slave. When they arrived in Petersburg, the woman sold Hester to slave traders for $750. Hester immediately filed a freedom suit, but less than a year later she died in jail at the age of 21.

“What is great about her story is there is a ledger book,” says Chris Smith, archival assistant. “On this one particular page there’s a list of names, purchase prices and sale prices. Across from Hester’s name you see her purchase price, but where the sold price would be is written the word “free.” So that started the whole thing. We were trying to figure out, what does this mean? We found the freedom suit she filed and we were able to corroborate her story as well as (read) a circular from a New York City abolitionist that told the story. It’s pretty remarkable to be able to piece something together that powerful,” says Smith.

Other stories the project revealed include a glimpse at the experience of Dennis Holt, a free black man residing in Campbell County who petitioned to be re-enslaved so he could be with his enslaved wife. Another story involved Rachel Findley’s yearslong fight to win freedom for herself and nearly three dozen descendants in a Powhatan County court. She won.

THE IMPORTANCE OF VOLUNTEERS

Asking the public to transcribe helps the library, which has limited staff for a project that could be ongoing for many years. “We just need to have the manpower to go through each record,” says Smith. “It takes time to go through court cases, which can have up to 300 pages. It’s really about trying to get enough manpower to dig through the records and then to index them and put them in spreadsheets that get turned into metadata, which is used when people search the website. But we also digitize them, too. That is time-consuming as well.”

After a document is transcribed, the image is uploaded onto Virginia Untold, says Crawford. “That’s why we want to encourage as many people as possible to be a part of the project. The more they get transcribed, the more we can put on Virginia Untold. We have 40,000 records and many of them still need to be processed, especially if they have a lot of narrative content to them.”

Another goal for inviting the public to read the documents is to generate community engagement. “We don’t have the time to read every record,” says Smith. “So with a lot of these documents, the people who are transcribing them are the first people to read them in maybe 150 years. It helps us out with a full text, searchable document that is legible, but also we want to engage the community around us to let them know about the project and to also be involved,” says Smith.

So far project organizers have been astonished by the number of users, from across the nation and in Europe.

The Library of Virginia is currently looking at how best to get feedback about the project, specifically what people like and dislike, what they are learning and how they are using it. “We want to know how people are using the information they are finding in the records,” says Crawford. The software will also capture demographic information so they know who is using it. Are the users private researchers, university professors, genealogists, public school students and teachers, and novelists? “We want to get as much information to better serve our users and identify records to put out there,” says Crawford.

The first phase of the project, which began in summer 2013, is wrapping up. “I’m not sure how many phases there will be,” says Crawford. “We want to wait until we get the feedback … before deciding what to do next. This is the initial release, so we want to give it time to breathe and get some reaction. Some of the feedback I get from presentations are that people are enthusiastic, but we hope to get some concrete feedback from the evaluation resource.”

Such feedback will help with grant applications, as additional funding is needed, Crawford says. “This is a longtime project. We have many, many records here. We’re just a snowflake on top of a larger iceberg right now with this project.”

Wooding agrees that the project requires patience and persistence while providing a powerful payoff.

“I enjoy history, and this is sort of like archaeology where you are digging and hauling dirt and you’re finding bits and pieces, and someone else will put the bits and pieces together and make stories out of them. And this shoveling work is making this material available to other people.”

Robin Farmer, an award-winning journalist with more than 25 years’ experience, has worked as a staff writer for The Hartford Courant and the Richmond Times-Dispatch, where her work earned her a Knight-Wallace Fellowship at the University of Michigan, among other national honors. She focuses on health, education and business topics as a freelance writer. Farmer also writes fiction and is working on her debut YA novel.