A Portrait of Women in 1969

The elements marking the changes

The early baby boomers were donning caps and gowns in 1969. Richmond was very much an urban college town, and record numbers of first-generation college women were graduating from the city’s three universities. It was a new day for educated women. Well, not entirely a new day. More girls were going to college, but the culture was still telling young women to get married and have children before – or perhaps instead of – pursuing a career.

“Enjoy your career years, girls,” my home ec teacher used to say. “Those few years fly by, and then you’ll be home with your children.” Nobody in the class questioned that statement. Indeed, we were getting the same message from family, church and TV. The Mary Tyler Moore Show – one of the first popular shows to feature an independent woman – was not to make its debut until a year later. The “Big Three” careers for women were still teacher, nurse and secretary. Of course, there were exceptions, like airline stewardess, but you had to be thin, pretty, single and plan on a short career. My mother held a women-only job – stenographer – a job, like telephone operator, that is completely unknown to young women today. If you had asked me about “STEM” in 1969, I would have thought you were putting together a floral arrangement.

In 1969, marriage came before babies. There were a few girls who got it backward. They went away for a while, or planned a rushed wedding. The term “single mother” meant someone widowed or divorced. But that was starting to change.

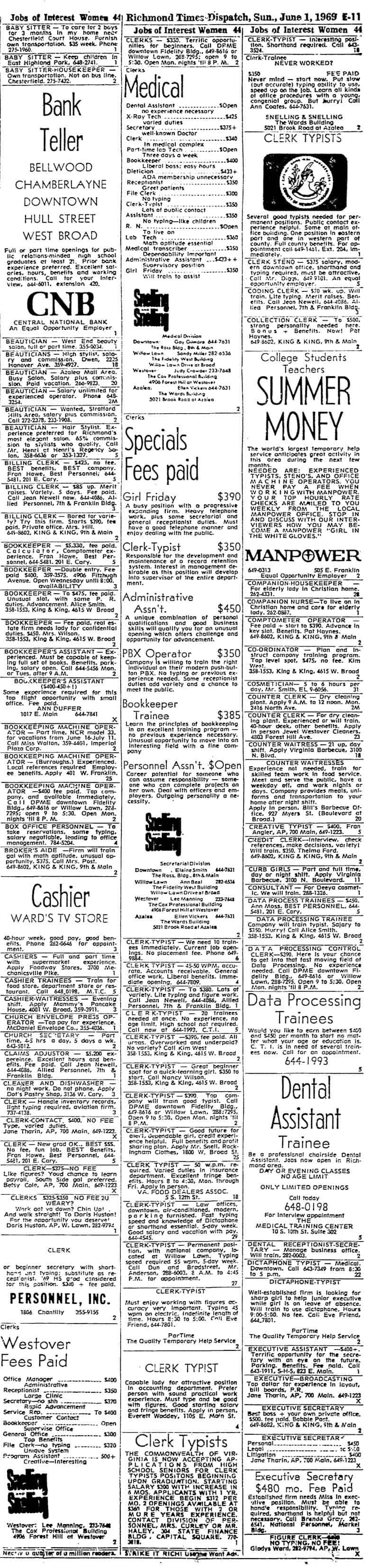

Emboldened, we broke the rules like water rushes over a broken dam. We didn’t know it then, as we pored over the “Help Wanted – Female” classified ads, but we were about to approach the “glass ceiling” (a phrase to be coined 10 years later), and the separated ads themselves were about to go the way of bouffant hairstyles and girdles.

We were getting past the front offices, but we were still getting sent home for wearing pantsuits. Undaunted, we started wearing the new “mini-skirts,” and our skirts moved up from our knees to our panties. We tossed garter belts for pantyhose, and in a couple of years, some of us would be tossing our bras as well. Some of us were sporting “hot pants,” never dreaming that our fashion courage would evolve into the yoga pants of our golden years.

BEYOND THE HOME AND OFFICE

Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” had gotten our attention, and we put her thoughts (“Find out what it means to me!”) into action. We had discovered Janis Joplin a short time earlier, and a lot of us wanted to look and act just like her.

The year 1969 was very much a year of protest. It started with college dress codes and escalated to Civil Rights and the war in Vietnam (which took our brothers and boyfriends), and eventually we protested for women’s rights. If you had told us then that college dorms would later become co-ed, that gay marriage was on the horizon or that we would find dates “online” (whatever that was), we would not have believed you.

Scores of women, mostly a little older than the boomers, were galvanized by Betty Friedan’s new book, The Feminine Mystique, the inspiration for the National Organization for Women. By 1969, it was the talk of the nation. Thanks to Richmond activists Zelda Nordlinger and Mary Holt Carlton, the founding of a Richmond chapter soon followed.

Women’s Rights took off fast and was a movement not to be ignored. However, in 1969, there were two strains of the movement. There were the NOW activists, and there was an alternate branch of feminists, who called themselves “radical feminists” or “women’s liberation.” These were generally the younger women of a counterculture, who formed from college unrest and an overall reaction against the war, racism, poverty and other radical causes. They considered NOW too mainstream. Both groups were picking up steam dramatically in 1969, but the mainstream feminists had more staying power, with a push to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. The ERA is still on the agenda to this day, with Richmond as “ground zero.”

We protested that women were left out of our college courses. We didn’t know that we were paving the way for the formalized women’s studies curriculum offered today, and we had even less of a clue that gender studies would be conceptualized soon after.

In the late ’60s, women started joining the new “sexual revolution.” Every popular magazine carried articles about the safety and glory of “the pill,” and unmarried women whispered about how to get it. We would never have believed that our children could someday buy condoms at any drug store. Abortion was illegal, but the procedure was available in some form, to both rich and poor, through underground networks inconceivable today. Roe v. Wade would legalize abortion five years later.

We had already fallen in love with The Beatles, and we kept going to concerts in droves. Many of us hitchhiked to Woodstock that year, and, much to our parents’ disapproval, young women could be seen thumbing rides, alone, in cities and cross-country.

We valued women’s right to vote, but in 1969, all young people had to wait until they were 21 to do it. Little did we know that someday we would have the chance to vote for a woman.

It was about that time that our language started to change. “Miss” and “Mrs.” were considered old-fashioned and “Ms.” was the new alternative. Some married women used double or hyphenated names. Some used their original names, though that never caught on widely.

We complained, at least among ourselves, about sexual harassment, but we never could have known that our daughters would start a giant campaign called #MeToo.

One question for women – and everybody else – hangs in the air: #What’sNext?

Bonnie Atwood is a writer and lobbyist based in Richmond. Her business is Tall Poppies Consulting. Reach her at Bonatwood@verizon.net.

SNAPSHOTS OF TIME

By BOOMER Staff

Reflecting the tenor of the time, newspapers and magazines demonstrate society’s “expectations” for women in 1969, sometimes in subtle ways.

For example, the Jan. 20 Richmond Times-Dispatch ran an article in “Accent on Women” on Mrs. Patricia Lancaster, “a trim young wife, whose husband Jim, is on loan to Ferrum from the teaching staff of Tennessee Technological University.” Both Lancasters had taken up karate while at Ferrum. The two photo captions proclaimed, “Petite Blonde Does Not Look the Part of a Karateka in Training” and “To Her Wife and Mother Role She’s Added Karate.”

On March 4, the paper ran a front-page story about a Westhampton College junior campaigning for lowering the voting age in Virginia from 21 to 18. Said the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “If legislators can be swayed by a dazzling smile, the Virginia General Assembly may be on the brink of giving the vote to 18-year-old citizens of this Old Dominion. A one-girl lobbying task force, Miss Helen Outen of Richmond, invaded the Capitol yesterday to encourage attendance at the ‘Vote 18!’ breakfast … Her smile and tact won a lot of admiration from the male politicians who abound in the legislative halls, and she qualified quickly as a leading candidate for the title of loveliest lobbyist at the extra session.”