Maya Rudolph’s Comedic Strengths

The comedian addresses burnout, impressions, and the link between music and comedy

Just where do Maya Rudolph’s comedic strengths come from? Variety writer Caroline Framke reflects on Rudolph’s background, inspirations, current projects, performing eccentricities, and thoughts on women in comedy.

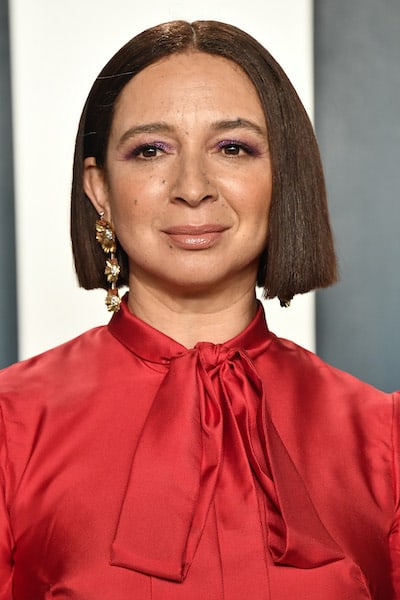

Image above, left to right: Ike Barinholtz, Tina Fay, Amy Poehler, Maya Rudolph, Jason Moore. Photo credit: Dwong19, Dreamstime.

When Maya Rudolph was a kid, she’d stage one-girl musicals in her living room and play make believe in empty corners of her mother’s recording studios, creating makeshift stages anywhere she could to satisfy her performing itch. Some 40 years later, though, she has so many platforms to choose from that it’s become genuinely overwhelming.

“Before any thoughts of quarantine, I was feeling very burned out,” she admits. “I was weirdly well on my way to retooling, and I think I’m still there. I feel less ashamed to admit that I would like to go a bit slower.”

Before the pandemic hit, Rudolph was booked solid. She had once again become an SNL mainstay to play then-Senator Kamala Harris, while her portrayal of a goofy, almighty judge on “The Good Place” made her one of the show’s most memorable guest stars. Her malleable voice had become ubiquitous across the wide world of animation, especially with her portrayal of a gleefully filthy “hormone monstress” on Netflix’s “Big Mouth,” a brilliant showcase for her ability to turn any single phrase (e.g. “bubble bath”) into a luscious dessert (e.g. “bwuuuuhbble bayaaaath”).

All three of those roles landed Rudolph Emmy nominations and then her first two wins in 2020. (The only reason she lost the third was because she had been nominated twice in the same category.) But the constant stream of obligations left her exhausted, burned out by her own enthusiasm for being a part of as much as possible, as often as possible. “I was just saying ‘yes’ to everything,” she sighs. “It took a toll, and I was tired.” So when the opportunity came for her to pump the brakes, she gratefully did.

Knowing which way to turn

Speaking from her home in Los Angeles a week after hosting “SNL” for the second time, Rudolph is contemplative about this potential turning point in her life and career. “Something that I feel has been a big awakening for me as I look at work is what makes me happy, what makes me unhappy, and how do I establish those boundaries?” she explains.

On a macro level, that might mean taking on fewer projects even if she loves everyone involved in them. On a smaller, more immediate level, that just might mean wearing whatever the hell she wants.

“Heels and I were already on the outs, but now we’ve gone our separate ways, which is fine by me,” Rudolph laughs. “And I no longer have a waist, so there’s that. My thighs haven’t seen pant legs in a year. I’m just going to become Elaine Stritch and wear a shirt.”

Even over Zoom, Rudolph already seems perfectly content with this ethos. Her distinctive voice turned down from 11, she blinks into the Zoom camera through clear-rimmed glasses, her dog Daisy curled in her lap. And while her flowered smock isn’t exactly the crisp white button-down for which Stritch became famous, Rudolph draws inspiration from brassy broads like her who insisted on being themselves, expectations be damned.

Going for the glam … or not

Take Rudolph’s comedic idol, Madeleine Kahn, a forcefully funny woman whose impeccable glamor came arm-in-arm with her ability to make every line a standout. Growing up with Mel Brooks films as a household staple, Rudolph would watch in awe as Kahn outshone everyone else as an impetuous empress, a jaded madam, a film noir heroine climbing out of a pristine Cadillac in a matching jumpsuit. Rudolph didn’t have to know exactly what Kahn was imitating to know that she was always, as Rudolph puts it, “the beautiful woman doing something hilarious.” Later, as she became more aware of comedians like Catherine O’Hara, Gilda Radner, and Jan Hooks, she realized this niche of comedian was her ideal. “Whether I realized it or not, I was watching these women that I wanted to be, who were gorgeous and funny – which to me is the ultimate combination of perfection,” she says. “They could just do anything.”

Then again, Rudolph’s also partial to less glamorous comedic turns, like so many of the scenes in “Bridesmaids” that made the movie such a standout 10 years ago. While her infamous “shitting in the street” moment was mostly just stressful – you try sliding to your knees in a wedding gown across a full lane of traffic – she fondly remembers the setup of everyone sweating through food poisoning before all hell breaks loose. “Knowing what was coming and everyone having to hide it, constantly being sprayed down with everyone in different stages of duress … it was just a really fun slow burn,” she recalls with a laugh. (More than anything else with “Bridesmaids,” Rudolph remembers laughing.)

She grew up with a keen eye for what makes performers great, not least because she spent her early childhood watching her mother, the singer Minnie Riperton, dazzle crowds on tour. As she watched musicians crush their sets with wit and flair, she’d long to do the same. “And then I’d see something funny, like a movie or a comedian, and think that I want to be like that, too,” she adds. “It wasn’t tangible to really understand what it was, but some magical quality.”

She quickly came to revere this indescribable connection between music and comedy, the two defining creative forces of her life. “They’re kind of the same language, weirdly,” she explains. “They’re both things that, when they’re done well, they can’t really be taught. You’re either good at them or you’re not.”

Maya Rudolph’s Comedic Strengths

Rudolph will soon get a musical comedy opportunity like never before with a juicy villain role in “Disenchanted,” the highly anticipated sequel to Disney’s “Enchanted,” starring Amy Adams as a wide-eyed princess navigating modern New York City. In a follow-up call the day after the table read, Rudolph gushed about the lively “school play” vibe of the movie and the delicious pleasures of getting to play a villain with “Dynasty”-level camp. (“It’s so dramatic!”)

“If this had been 15 years ago and someone asked if I wanted to be the bad guy, I might’ve been like, ‘geez, I don’t know,’” she says. “But I’ve come to learn in my many years that the most fun thing to get to do is when you get to play The Most.” She also recounted director Adam Shankman approaching her about taking on the part, and how gratifying it was to realize that he knew exactly why he wanted her for it. “It’s nice to be in a place work-wise where I feel like a lot of what I’ve done can speak for itself,” she says, “so I don’t have to explain who I am or what I do.”

Because as anyone who’s seen even a minute of her performing will know, so much of Rudolph’s comedy is intrinsically musical. Every one of her characters, whether Beyonce or a Bronx mom or a dizzy game show host, speaks with an infectious, uniquely bizarre lilt as Rudolph wraps her voice around their lines. Her Beyonce impression in particular came almost as second nature. As a fervent fan, Rudolph says, she’d already been paying such close attention to how Beyonce composes herself that when it came time to imitate her, it felt like “when you’re telling a story about a friend, and when you say what they said, you say it in their voice.”

Rudolph’s skill at twisting a single word into a wonderfully weird waterfall of sounds is unparalleled; she doesn’t have to be telling a joke to be hilarious. So it’s unsurprising to learn that Rudolph might feel most at ease in the voiceover booth, where she’s been able to experiment since her SNL days of volunteering for whatever narration might be needed that week.

“It’s probably where I feel the most myself: not on camera, and not a musician, but sort of a blending of the two,” she muses. It’s also thrilling for her to step outside her own body to be anything at all without limitation. On “Big Mouth,” for example, she portrays everything from the Hormone Monstress to a school principal to a dirty pillow. “It really feels like a place of freedom,” she says of her prolific voiceover work. “You’re not limited to male, female, human, animal, monster, whatever you’re made up of. That’s a place where I feel very comfortable.”

‘A Woman in Comedy’

It doesn’t escape Rudolph that she’s spent a lifetime defying categorization both through her comedy and as a person. “As somebody who’s not white, not Black, not just mixed, but my own particular mixture of mixed: Jewish, and speckled, with a big nose … I always identified as being very singularly myself, and not really belonging to any club,” she says.

The scrutiny crept its way under her skin, but now, she reminds herself that other people’s attempts to label her says more about them than her. “People really try to figure out who or what you are because it makes them comfortable,” she insists, as forceful as she’ll ever get throughout our conversation. “It doesn’t have anything to do with me.”

And that, ultimately, is where she also lands on the age-old question of what it’s like to be A Woman in Comedy, which plagued her at SNL and reemerged when “Bridesmaids” dared to spotlight funny women with no qualifiers (and very few men). When asked if the conversation has changed at all since, she’s wary in a way that makes it clear just how many times she’s had to go down a road she finds truly frustrating. “I feel like it’s my obligation to continue doing what I do best as opposed to, like, methodically thinking about my gender in order to be funny or not,” Rudolph shrugs. “I don’t give a fuck about that stuff.”

As Daisy clambers off her lap, Rudolph sighs and adjusts her glasses, as if making sure she can see her next point clearly enough to make it. “It’s a funny one,” she says, “because the minute I stick my toe into the conversation, I feel like it allows the conversation to exist … this leftover conversation that won’t die.” She rolls her eyes, cocks an eyebrow, lets loose the ghost of a grin. “In reality, it’s like we threw a great party, and then somebody walked in and was like, ‘wait, this is a girls’ party!’ And it’s like, ‘uh, what are you talking about? It’s just a party.’”