Heritage Instruments

Virginia luthiers, heirloom guitars, centuries-old traditions

“But for the grace of God, I would be a tree in the forest.” So reads the inscription on the back of a 16th century violin, belonging to late fiddle guru Vassar Clements. Luthiers in Virginia’s mountain region craft heirloom instruments that embody centuries-old cultural traditions. From 1700s settlers and African American slaves to the legendary Wayne Henderson, Virginia guitar makers create acoustic masterpieces.

Master luthiers Brian Calhoun and Randall Ray huddle over a workbench in their downtown Charlottesville shop, assessing a recently built dreadnought guitar. They’re debating the merits of a new water-based finish, which spreads on thinner and should minimally impede the wood’s natural resonance. It’s also more ecofriendly than oil lacquers.

“The catch is, it’s more work,” says Calhoun, 40, who founded the Rockbridge Guitar Company with Ray in 2002. But the method brings more than acoustic benefits. “It gives you the heirloom look of [a pre-World War II] varnish,” Calhoun continues. The finish “subtly conforms to the wood in a way that, to me, looks much more elegant than the perfect, flat, plastic-looking sheets produced by most modern finishes.”

Handcrafted impeccability

The immaculacy of the instrument’s craftsmanship is apparent. The top is carved from hand-selected Appalachian red spruce, which is widely regarded as the planet’s finest tone wood for acoustic guitars. It features a tobacco-colored sunburst finish that fades from a spotlight of bright graininess at the sound hole to an inky auburn darkness around the edges. The top is attached to the body by a blonde, figured maple wrap inlaid with abalone. The sides and back are made of rich, thick-grained mahogany. The neck boasts a fingerboard carved from sustainably harvested rosewood and beautiful custom inlays – Father Time blowing a tsunami of musical-note-filled sand toward the headstock.

The instrument exudes the eye-grabbing presence of a work of fine art. When Calhoun scoops it up for an aural test drive, I almost cringe. Is this beauty really meant to be fondled by human hands?

The art of music

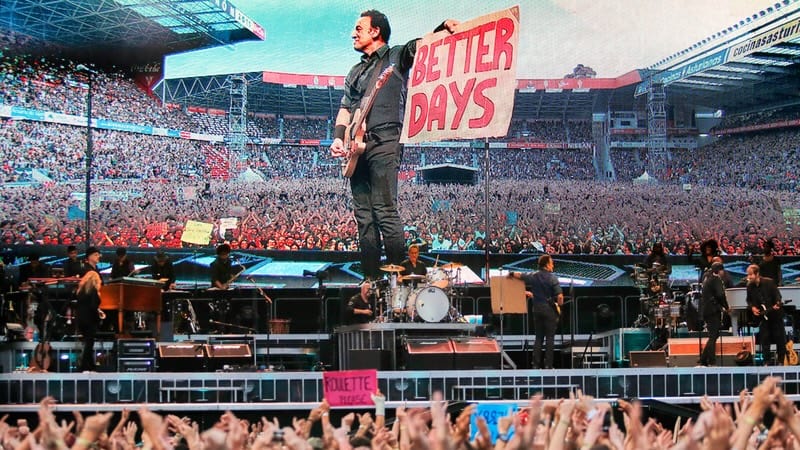

Then he picks through the opening lines of Tony Rice’s “Shenandoah.” The tone is booming, with rich and robust lows, muscular mids and chiming bell-like highs. Calhoun’s musical prowess is startling. It’s obvious why top-tier musicians like Larry Keel, Dave Matthews, Tim Reynolds, Warren Haynes and countless others own and play Rockbridge guitars. Incredibly balanced, they sound like a sonic miracle made manifest.

“We pay meticulous attention to every last detail and do it all by hand,” says Calhoun. To ensure quality, the four-man team caps production at 60 instruments a year. Time-tested techniques are augmented by technological advancements like the above-described finish. Guitars start around $5,500, and demand is high. Turnaround from order to delivery averages a year to 18 months.

“Our goal is to build world-class heirloom instruments,” says Calhoun. “Randall and I want these guitars to be getting passed down through the generations long after we’re gone.”

Roots & branches

The focus on legacy stems from the men’s relationship. Ray is 57 and helped Calhoun perfect his craft as a teenager. For his part, Ray has lived in Lexington for nearly 40 years and says he learned the art from books and kindly old-timers in the Shenandoah Valley and southwest Virginia. He and Calhoun recently trained another luthier, who’s in his mid-20s. They envision Rockbridge as a boutique C.F. Martin & Company, which was founded in 1833 and is still going strong.

For Calhoun and Ray, making guitars isn’t just a business: They view themselves as torchbearers for the centuries-old musical traditions of Virginia’s mountain region.

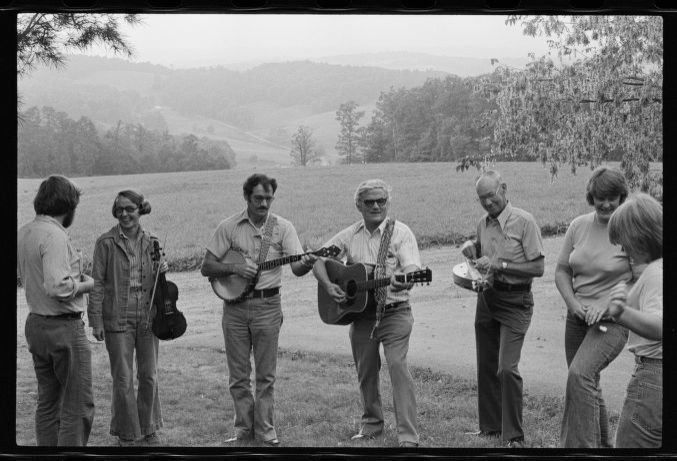

“We’re a byproduct of the rich and lengthy DIY culture of Appalachian musicianship,” says Ray. He and Calhoun’s path to becoming renowned luthiers started with playing bluegrass and old-time music. Picking on front porches and at festivals like the annual Galax Old Fiddler’s Convention introduced them to a culture defined by informal apprenticeships and skills that were passed down from generation to generation.

Calhoun and Ray seek to make guitars that embody those traditions.

“I don’t mean to wax mystical, but I think of instrument-making, like, you’re trying to give birth to this living thing,” says Calhoun. Achieving that takes more than skill. You’re seeking to craft a vessel that can be filled “with the history, love and joy of generations. Otherwise, it won’t sing, it’s just a box of dead, fancy-engineered wood.”

The regional ecosystem of Virginia guitar makers

As it turns out, Rockbridge is one of a handful of similarly minded heritage guitar-makers in the central and southwestern mountains of Virginia.

“Instrument making has been a part of communities in these areas since the 1700s,” says emeritus director of Ferrum College’s Blue Ridge Institute & Museum, Roddy Moore. Settlers brought violins and dulcimer-like stringed instruments with them from Europe. Precursors of the banjo were introduced by enslaved African Americans. Further, early versions of six-string guitars began to appear around the mid-19th century.

“Music has been a big part of life here,” says Moore. Family and communal gatherings almost always featured a fiddler, but additional players were welcome. Accordingly, musicianship came to be highly valued. Enthusiasm around the activity grew with time.

Every town came to have its stars, and when they all got together, it was a big event, says Moore. Consequently, the region became a breeding ground for roots musicians and amateur groups.

Melodies of diversity

Traveling minstrel shows in the mid-to-late-19th century introduced new, African-influenced sounds to the musical melting pot. The establishment of regional radio stations and live shows in the early-1930s brought paid work for local talent – and gave rise to stars like Kentucky’s Bill Monroe, who is credited with inventing bluegrass in the 1940s.

From the early days, adventurous woodworkers tried their hand at making homemade instruments. Most did so part-time, at the behest of musically inclined friends and family members. But a few mastered the craft and became regional legends. They began to attract apprentices and, like the music, skills were passed down through time.

“If you look at Virginia’s most reputable [acoustic] guitar-makers, the ones that have national and international followings?” says Moore. “Every one of them has ties to that lineage.”

Rockbridge is a go-to example. Similarly, another is Staunton’s Huss & Dalton Guitar Company. Founded in 1995 by Jeff Huss and Mark Dalton, the 13-person operation offers eight standard models for sale and four signatures, including a trio of collaborations with country music legend Albert Lee. Their shortlist of star customers includes Mary Chapin Carpenter and Paul Simon.

The towering spruce

When asked about influences, Huss, Dalton, Ray and Calhoun defer to one man: Wayne Henderson.

“He’s the guru,” says Ray. “If you’re building acoustic guitars for a living, you know that name.”

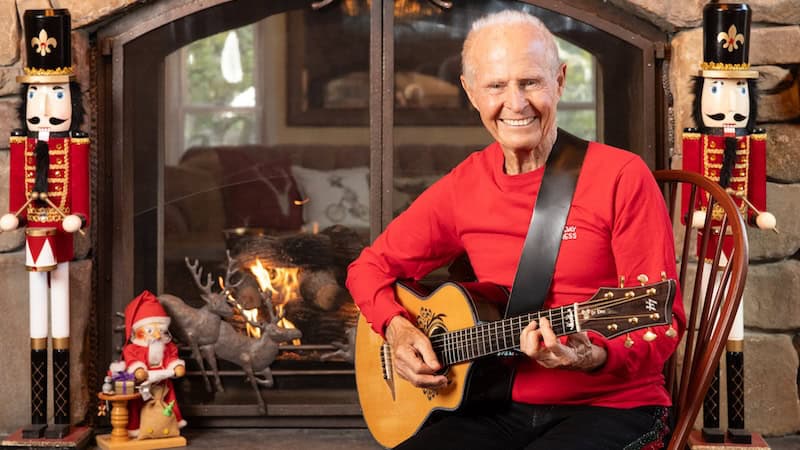

Henderson is 73 and lives near Whitetop Mountain along the North Carolina border. He learned woodworking as a kid, from his mother and grandfather, who made toys and coffins, respectively. Likewise, music ran in the family, and Henderson took up guitar at age five. So, as a teenager, unable to afford a Martin, he tried to build one from an old hardwood dresser.

Though the project failed, Henderson was hooked. Searching for a luthier to apprentice with led him to Albert Hash and his daughter/apprentice, Audrey Hash Ham.

“The two had a legendary reputation among regional musicians,” says Moore. “And if somebody was serious about learning, they’d go out of their way to teach them.”

Subsequently, Henderson became a fixture in Hash’s shop. He eventually parlayed the skills into a job in Nashville repairing guitars for stars like Elvis Presley, Neil Young and Doc Watson. International acclaim came in 1994 after Eric Clapton played one of Henderson’s guitars, tracked him down and ordered a custom instrument. Henderson famously added the superstar to his 10-year-long waiting list; Clapton’s guitar was delivered in 2004 and has since been featured on numerous albums.

Modern-day craftsmanship

So, today, Henderson works in a converted two-car garage beside his home in Rugby. He makes about 20 guitars a year and has built fewer than 800, total. His reputation as the Stradivarius of the acoustic has led resale prices to skyrocket to upward of $50,000.

The success has attracted numerous acolytes, including his daughter, Jayne Henderson. Now in her mid-30s, she left her job as an environmental lawyer to work as a full-time luthier with her father around 2016. As a result, Henderson says it’s a source of great joy to know she intends to carry his, the Hashes’ and their forebears’ legacy into the future.

“These instruments are more than simple wood and glue and metal,” says Jayne, echoing Calhoun. Preeminent luthiers are more than technicians. “You’re trying to create a living, breathing thing that a player can pour his or her soul into and make come even more alive. Simultaneously, it has to be built to last for hundreds of years or more.”

She says the approach is difficult but honest and profoundly special. Imposters beware: Making guitars in this manner can’t be achieved without a deep connection to and love for the music and culture of Appalachia.

Eric J. Wallace is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in more than 50 local, regional and national media outlets. Additionally, he is a contributing editor for Gastro Obscura.