Behind the Moon Landing and Looking to Mars

Digging deep at Langley

It was all hands on deck when Dennis Bushnell joined NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, in the mid-1960s. The Center, established in 1917, was rushing to respond to President John F. Kennedy’s May 1961 challenge to the nation to land an astronaut on the moon and bring him home safely by 1969. Langley was the first U.S. national laboratory devoted to the advancement of the science of flight.

“It was interesting and exciting here. It was a spirited time,” says Bushnell, then an engineer and now the Center’s chief scientist. “We were working with the Gemini and Apollo programs. We were hiring 150 to 200 people a year.”

The job required creativity, invention and “and great care, because we were trying to save lives,” Bushnell says. “Being on the frontier of just about every technology that existed, to a techie, there is nothing more exciting than that.”

Unlike today when computers spit out data instantaneously, Bushnell and others at the Center worked with hand-operated Friden mechanical calculators and slide rules. “There was a quiet sound of slide rules,” says Bushnell of the office atmosphere.

FINDING A WAY TO THE MOON

Many crucial questions needed to be answered before the agency could land a man on the moon safely. “We weren’t sure how their bodies would react,” Bushnell says of the astronauts. “We weren’t sure how our machines would work there.”

His work at the time concentrated on a radio blackout problem that was discovered during a previous mission. “Nitrogen in air breaks down. You build up electron concentration and radio waves won’t go through,” he says. “I worked on ways to predict when this would happen and other ways to use water droplets” to correct the problem.

He also worked on aerodynamic heating as it related to the Apollo space capsule. “We had to make it better. They told us to do anything we could to make sure the crew was safe,” Bushnell says.

Darrell Branscome, strategic integration lead for the Space Technology and Exploration Directorate at Langley, worked on issues related to the agency’s space programs. “Langley’s major contributions were successful re-entry, descent and landing back on Earth,” he says.

His contribution to the Apollo program was centered on thermal analysis, making sure the Apollo capsule didn’t “overheat while waiting to be launched,” he says.

Before the Apollo program, Langley led the Lunar Orbiter program, which produced five successful flights of mapping the lunar surface. The mapping was used to select landing sites for the Apollo missions.

HUMAN COMPUTERS CALCULATE THE FUTURE

During the ’60s Bushnell worked with the some of Langley’s female computers, a job title given to someone who performed mathematical equations and calculations by hand. The popular 2016 film Hidden Figures chronicled the work and the contributions of these women (men also worked as computers).

“We had a whole room full of these human computers running the Friden computers. It was a cacophony of noise. We would set up huge arrays of spreadsheets for them. They used them to do data reduction from the wind tunnel, flights, etc.,” Bushnell says. “They were a valued part, a necessary part, of the team.”

The best intellects in the nation were attracted to the Apollo project, he adds. “We had superb technical leadership. It was wonderful.”

DESIGN, TESTING AND FOOTSTEPS ON THE MOON

NASA Langley designed the Apollo command module as well as the lunar module, used for landing on the moon. The center conducted hundreds of hours of wind tunnel testing to help determine the aerodynamic characteristics of the Apollo-Saturn launch configuration. It also evaluated Apollo’s ablative heat-shield materials and structural integrity in numerous facilities, including the 8-foot-high temperature tunnel.

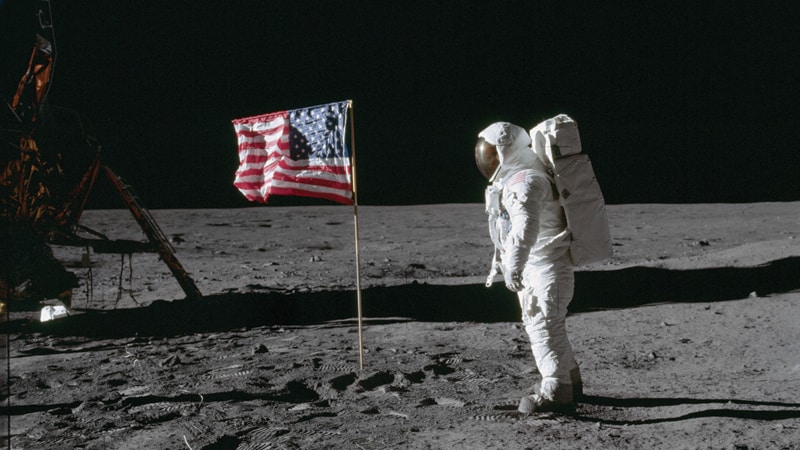

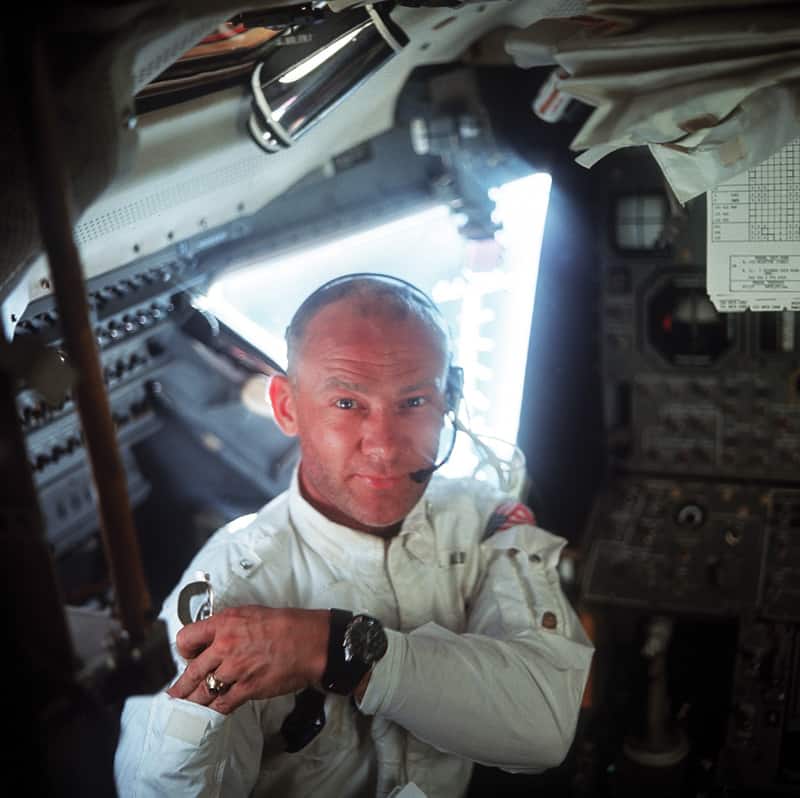

A number of Apollo astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, practiced lunar walking in Langley’s reduced gravity simulator, rendezvous docking simulator and the lunar landing training facility. The rendezvous-docking simulator is now designated a National Historic Landmark and sits in the hangar at Langley.

Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin – the crew of Apollo 11 – landed on the moon July 20, 1969. Armstrong later commented that the touchdown on the moon was “just like Langley.”

As they watched the moon landing, the staff at Langley was “very much aware of what was happening and how important it was,” says Branscome.

TO MARS AND BEYOND

TO MARS AND BEYOND

“We’ve been working in the last decade on new systems and capabilities that will take us to the moon,” says Walt Engelund, Langley’s director of space technology and exploration, “… expanding into the solar system and eventually landing people on Mars.”

Langley helped in the development of the Orion spacecraft, which will return to the moon and eventually Mars. It will carry a four-person crew to lunar orbit and rendezvous with “what we believe will be a gateway, a small waystation,” Engelund says. “It will allow them to stay 30 days and send astronauts back and forth to the moon. That will be a gateway to Mars.”

The agency believes that there are large reserves of water and ice on the poles of the moon, which Engelund says could be harvested for astronauts to use as water and hydrogen and as rocket fuel to go farther in the solar system.

Langley is also working on how it will communicate with astronauts on Mars. “If you go to Mars, there is a 20-minute lapse in radio communication each way,” Engelund says.

He doesn’t know exactly what Langley employees were feeling during the moon landing in 1969, but he does know, “We are getting some of that same excitement here to make all of this a reality.”

Award-winning writer Joan Tupponce writes about a variety of subjects – from business to celebrity profiles – for publications that include O, The Oprah Magazine, AmericanWay, U.S. Airways magazine and AAA World.